The test administered to tens of millions of men around the world each year to look for signs of prostate cancer in the blood relies on discoveries made at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center. The cancer center’s work to pioneer new and better ways of detecting cancer continues today.

It was a Roswell Park team working in the 1970s that discovered prostate-specific antigen (PSA), a protein in the blood that when elevated, can indicate prostate cancer, leading to the PSA blood test in use today. Previously, only 4% of prostate cancers diagnosed were curable; the number now stands between 80-90% thanks to earlier detection made possible by the PSA test.

Today, another Roswell Park team is working to build on that legacy, working to develop a urine test for prostate cancer — leading, they hope, to earlier interventions and more lives saved.

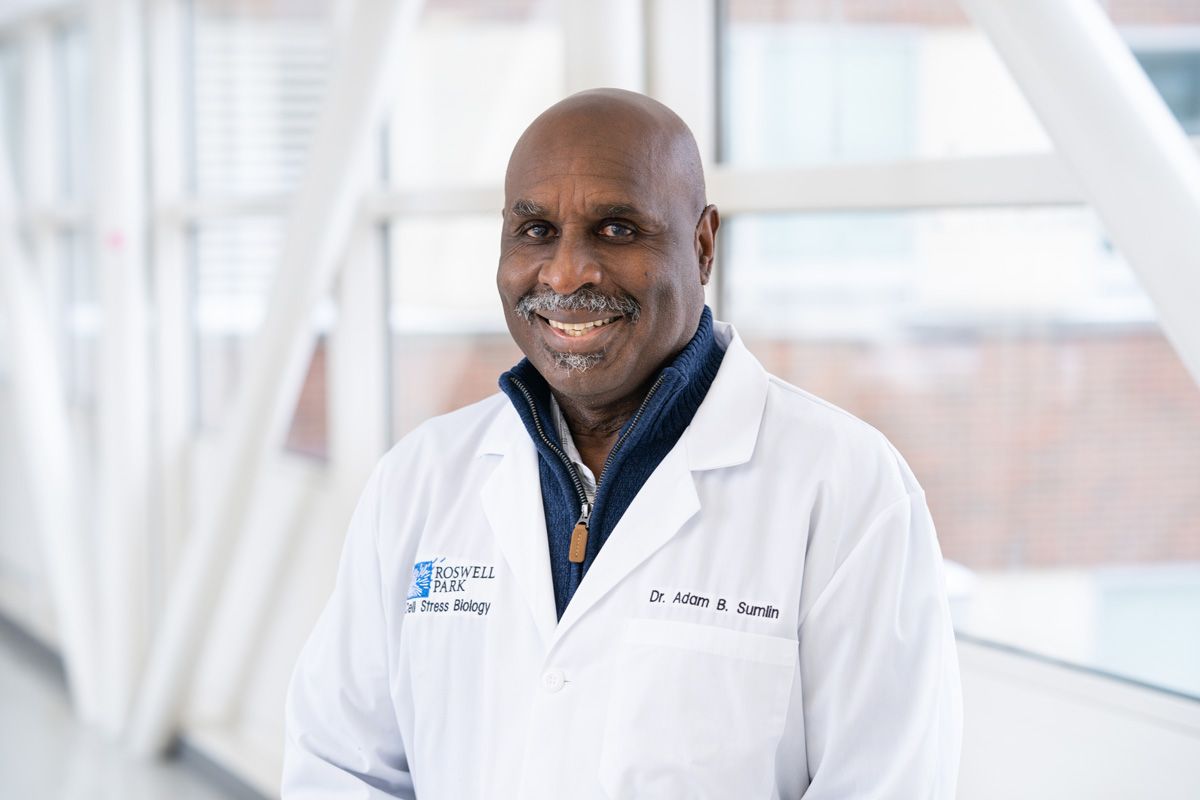

Adam Sumlin, PhD, MBA, is working on just such a test in the hopes of encouraging more men, especially more Black and Hispanic/Latinx men, to be screened earlier and more effectively.

Right now, most men are screened for prostate cancer through a blood test that looks for PSA biomarkers. While the PSA test has revolutionized treatment and outcomes for thousands of people with prostate cancer, improving the odds for what was at one time seen as a death sentence, the test has some limitations.

“The PSA is one of the first tests invented for early screening for prostate cancer, and has been an incredible benefit for people worldwide. The purpose of the PSA test is for detection, not for determining aggressive cancers, but it does return a number of false-positive results. The main problem is that it has a lot of false positive.

“Prostate cancer experts recommend that beginning in their 40s, men get both a PSA blood test and what’s known as a DRE, or digital rectal exam, which involves a physical examination of the prostate, a gland located near the rectum. But when you tell men that you want to do a DRE, they get very uncomfortable. When I thought about it, I thought, ‘What if I could find something that’s in the urine?’ Men do not mind giving you a sample of urine at any given time.”

This is especially important because not all prostate cancers need to be treated. In the effort to identify biomarkers in urine, Dr. Sumlin is working with Eric Kauffman, MD, and Khurshid Guru, MD, both in Roswell Park’s Department of Urology, to follow more than 120 men currently in active surveillance for prostate cancer. These men are regularly checked to see whether their PSA levels indicate that their cancer has progressed to a point where treatment is needed. The team is looking at both urine and blood PSA test results to monitor participants’ PSA levels over five years.

This initiative has been in the works for about three years now, and when the Buffalo Bills Alumni Foundation first heard about Dr. Sumlin’s research on prostate cancer, it provided him a $100,000 grant in support of his work.

More than just improved testing

But Dr. Sumlin doesn’t want to just find a better screening test for prostate cancer. He wants to help men understand their options when it comes to addressing the disease earlier, as many patients don’t even know they have a prostate until they develop prostate cancer.

“Prostate cancer is something they call an old man’s disease,” Dr. Sumlin says. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) currently recommends regular prostate screenings for men between the ages of 35 and older, with the belief that, from the age of 65, it’s more common for men to develop the disease. “The difference there is, once you get to 70, surgery isn’t recommended, because you won’t die from your cancer. Prostate cancer is a slow-growing disease.”

Between the ages of 35 and 65, however, some 33,000 men die from prostate cancer each year, out of 264,000 men diagnosed with it annually.

If prostate cancer is found early in younger men, they have more treatment options other than a prostatectomy, or surgery to remove the prostate, Dr. Sumlin notes.

When PSA levels increase in younger men, they’re more likely to take a wait-and-see approach if they’re told treatment could affect their intimate relationships. “They’ll say, ‘When it gets bad, then you can see me.’ But when it gets bad, what decision will you make? What treatment will you get?”

He’s also working to develop an educational approach that would inform men of various treatments they may be able to choose from, including chemotherapy, radiation, hormone therapy and immunotherapy, along with discussions on how to understand the financial stress they might feel in making healthcare decisions.

Informing the community with a united message

Collaborating with specialists across our community is also important to Dr. Sumlin. He’s working with Ali Houjaij, MD, and Oussama Darwish, MD, in the urology department of the U.S. Veterans Administration and Michael Hanzly, DO, from Buffalo Medical Group to make sure men across Western New York receive consistent information about their options for prostate cancer treatment wherever they see their doctor.

Prostate Cancer Diagnosis

Get more information about the current methods of detecting prostate cancer.

Learn More“Every year or two, we hold a seminar, either in-person or virtual, to discuss the needs of having these discussions about financial toxicity and of the questions men need to ask their doctors,” Dr. Sumlin says. “We’ll also put together some patient advocates to go out with us into the community and discuss this with men. These advocates are young men who are prostate cancer survivors.”

This outreach will focus on Black and Hispanic/Latinx men, because they face a higher risk of developing prostate cancer at a younger age.

It all ties together with his drive to develop an easier test for biomarkers of prostate cancer.

“That’s the purpose of wanting to find a biomarker for urine. Now we can say, ‘You have this, it’s at this stage, we can start giving you chemo or radiation or hormone therapy or immunotherapy,’ ” he says. “I want to reach out and expand the program so that throughout the community, we’re delivering the same message. That’s going to not only help the patients, it will give them a better idea of how to make a decision and how to react.”