Colorectal cancer is curable if caught early, and the way to catch it early is through a colonoscopy.

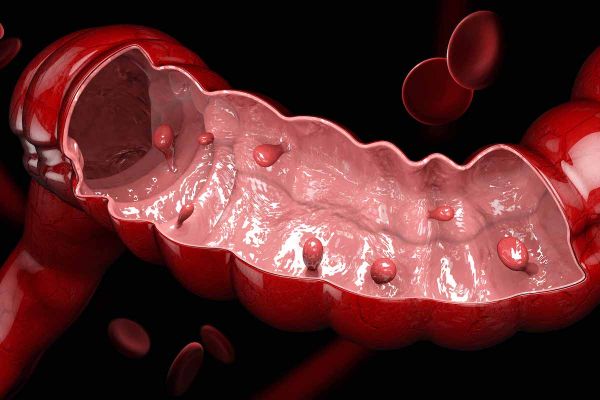

That makes it different from nearly every other kind of cancer: all other screening tests and early detection methods are looking for the presence or absence of cancer, but colonoscopies can identify precancerous growths in the form of polyps that can be removed before cancer has a chance to develop, says Kathryn Glaser,PhD, co-leader of the Cancer Screening and Survivorship Program at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Unfortunately, people don’t receive the same kind of messaging and warnings about colorectal cancer as they do about breast, prostate, lung and other kinds of cancers and, as a result, the rate of colonoscopies conducted each year is considerably less than for mammograms and other tests, she says.

Although deaths from colorectal cancer have decreased in recent years, it remains the third-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men and women and is expected to be linked with some 53,200 deaths this year alone.

An estimated 90% of people who die from colorectal cancer are over the age of 50, but people under the age of 50 who are diagnosed with the disease are more likely to have advanced cases. This year, an estimated 12% of colorectal cancer cases will occur in people under 50, following a trend of higher rates of colorectal cancer in younger adults that has been tracking since the mid-1980s.

Partnerships help reach underserved communities

Roswell Park partners with several Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHCs) in Buffalo and across Western New York to provide education and access to testing for people who may have difficulty getting access to the care they need, including Buffalo’s growing immigrant and refugee population.

Working with partners like Jericho Road Community Health Center and its majority non-native English-speaking clients means many of the educational handouts and materials provided need to be easy to understand, including diagrams and photos explaining some health checks. Roswell Park has been working with Jericho Road since 2016 and it was there that the health educator program was created. Roswell Park also partners with Neighborhood Health Center in Buffalo and Erie County Cancer Services Program and has recently received grant funding to expand its health education program to work with rural FQHCs like Universal Primary Care in the Olean area and the Chautauqua Center in the Jamestown area.

“These partnerships support our outreach and engagement efforts as well as build relationships with community gastroenterologists with the goal of increasing community cancer screening rates over time,” Dr. Glaser says. For the past two years, it has been even more difficult to get people to come in for cancer screenings of all kinds, due to hesitancy and concerns about the COVID pandemic, but “it’s really important to continue to get screened. We want people to know there are alternatives available for people who are afraid of going to facilities to get a screening colonoscopy. We moved to stool-based tests since the pandemic started to make sure people continue to be screened.”

Life has opened back up. Now it’s time to get back to health.

If you’ve waited to schedule your cancer screening, delayed your doctor’s appointments or are ignoring that lingering symptom that is just not right – now is the time to act.

Learn MoreOne benefit of working with FQHCs like Jericho Road is that people receive a referral from their primary care physician, and our patient navigation team continues to work with the patient and their doctors to make sure all tests are completed and can explain any and all test and screening results.

“We’re partnering with primary care doctors who are coordinating care. They refer patients for screening and pass them off to our navigation team,” Dr. Glaser says. “We educate and we help address any barriers to care by coordinating scheduling, transportation services, language services and whatever other needs might arise. We make sure they get to their screening appointments. When it comes to a stool-based test, we follow up with phone calls to make sure the test has been completed, returned and the results are understood.”

Working with primary care doctors and FQHCs is important because “instead of just calling someone, the recommendation is coming from their doctor. That’s an established and built relationship of trust,” adds Alyssa McNulty, a community relations coordinator in the Cancer Screening and Survivorship Program.

Patients who do not currently have health insurance can receive care by working with the New York Cancer Services Program, based at the Erie County Department of Health.

Don’t be afraid to ask about family history

Another bump in the road when it comes to colorectal cancer screening in particular is the way the test is conducted: the most accurate screening involves a colonoscopy and the use of an internal camera to look for those precancerous polyps that can be removed before becoming problematic.

“We’ve found in our work, in many cultures, it’s a big ‘no way’ when you start to talk about colonoscopies,” Dr. Glaser says. “The same is true for prostate cancer. There’s a lot to overcome when it comes to the modality of screening for colon cancer. But a colonoscopy is truly a preventive form of screening. We try to stress that. Stool-based tests are less ideal because you aren’t removing polyps when they’re precancerous cells; you’re looking for the presence of those cells. Some of the DNA-based tests are more sensitive to that.”

It’s also important for people to talk with their families about their cancer history, something else that might be culturally unacceptable or difficult.

“In some communities, you don’t talk about family or personal business, you don’t talk about cancer, so you might not know a first-degree relative had colorectal cancer or breast cancer or prostate cancer,” Dr. Glaser says. “It’s so important to talk about risk because it impacts the people who should get screened and when.”

The recommendation of the American Cancer Society and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network is for colorectal cancer screenings to start at age 45 for people at average risk of developing the disease; for people with a first-degree relative who was diagnosed with colorectal cancer, like a parent or sibling, that recommendation changes to one year younger than the relative’s age at diagnosis.

“Fundamentally, we want our community to be healthy and strong and live a long and healthy life,” Glaser says. “We want them to be there for all of the big moments.”