Summer internships are an important part of the college experience, allowing students to implement some of the skills they’ve been learning toward their future careers.

But how often do those internships involve working side-by-side with cancer researchers, well-respected experts in their fields, and earning a co-author notation on papers?

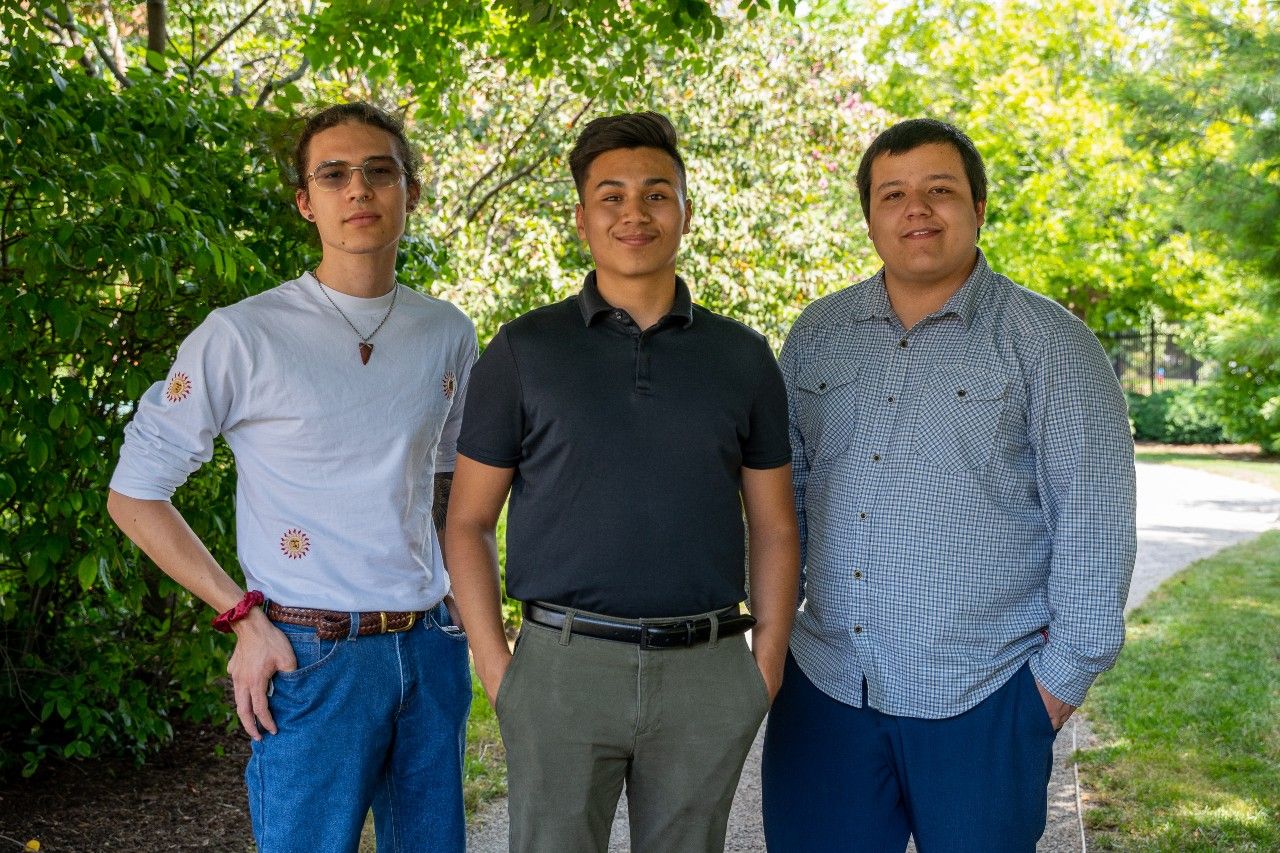

For Dakota Lazore-Swan, Flint Swamp and Jake Maresca, that’s exactly how they spent their summer, working for 10 weeks with doctors and nurses at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center as part of a partnership between the Department of Indigenous Cancer Health and the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe (SRMT) of Akwesasne, funded by the National Institutes of Health. They also attended the Association of American Indian Physicians’ 50th Annual Meeting and National Health Conference in Washington, DC, in July, spending a week with other students and medical leaders. An additional 14 high school students participated in a four-week summer program with Roswell Park to learn about cancer and social determinants of health.

For these college students, it was their first opportunity to take their education out of the classroom and get a feel for what a career in medicine and research might look like.

Dakota, a rising junior at St. Lawrence University, worked with Rodney Haring, PhD, MSW, Director of the Department of Indigenous Cancer Health and William Maybee, Outreach Coordinator on a project called ROOTS. “It’s about Indigenizing colorectal cancer screening. Native American men in particular are more likely to get diagnosed in later stages of cancer, so we’re trying to encourage more people to get screened. I worked with my mentors a lot and they put me in contact with different physicians because I’m interested in medical school.”

Flint, a rising sophomore at Syracuse University, worked on a research project studying the amounts of carcinogenic contaminants found in fish. “I chose the fish population because where I come from, there’s a lot of fishermen. It’s a traditional way of food; it’s very popular among families. I really wanted to bring this work back home. If there are contaminants in the water and the fish people eat in Western New York, there have to be contaminants in the fish and water around the St. Lawrence River,” near where he and Dakota grew up.

Jake, a rising senior at Saint Joseph’s University, worked with nurse educators on a feasibility study for a device that can determine whether chemotherapy is leaking treatment into a patient’s vein. “The device uses a light sensor to detect changes in the way light passes through skin and tissue and that’s how it determines whether a leak is happening. Other devices, like pulse oximeters, have a bias and can’t measure oxygen levels accurately in people with darker skin tones. I was wondering whether this other device had the same bias or is impacted by skin tone. I suggested that and developed part of the methods that can be used to take that into account. I was working within the framework of the research the nurses are already doing, but I was able to direct it in my own way.”

Setting the stage for their futures

In addition to their individual projects, all three students were able to hone their skills in literature reviews to support their work and contributed to papers that might later be published in journals.

They realize, too, that there’s a lot of room for growth and change in the medical field.

“The AAIP conference in DC was a lot of fun. We talked a lot about the amount of disparity when it comes to American Indians in medicine. The statistics show there aren’t many professors who are American Indian, Alaska Native or Native Hawaiian,” Dakota says. “No Native person has ever filled the role of dean in a medical school.”

“Less than 50 full professors across the country are Native Americans in medical schools,” Jake adds. “The conference itself was really a place not just for physicians but aimed at other health professions, too, and geared at improving care for Native doctors. Dr. Haring gave a talk about the work he’s done.”

“We’re pushing for growth in the health professions,” Flint says. “Trying to help medical students and undergrads with their future. It’s not common – I’m lucky to have the amount of people who are like me at my school,” he says. Having a whole week together at a conference filled with people who looked like them was a first."

At St. Lawrence, there are only five Indigenous students in total, Dakota says, including a Native Hawaiian and an Alaska Native. “Five students out of 2,000. And we’re about an hour from the reservation where Flint and I grew up. That’s one reason I want to work toward a scholarship, to provide more resources toward it. If we can have scholarships for students from other countries, why not?”

Excited for what’s next

As they head back to school for their fall semesters, Dakota, Flint and Jake feel more prepared to continue studying medicine. Jake, a nursing student, has decided to pursue his doctorate in research, something he credits his mentors at Roswell Park with inspiring. “They started campaigning for me to get my PhD, so that’s what I’ve decided. I’m going to come back next year and apply for the nursing PhD program (at the State University of New York at Buffalo). I’m hoping to get a job at Roswell Park as a nurse and I’ll be able to continue my research I’ve been working on this summer. When all these opportunities kind of lay right in front of you, I think it’s a good idea to take them.”

Dakota says he’ll continue to work on data analysis of his research with the goal of getting it published. “Having my name on a paper will go a long way for sure. I’ll continue to prepare for medical school. I think I’d like to be a doctor in radiology.”

Flint, who still has a few more years of undergrad left, wants to continue working toward a career in healthcare. “At first, I wanted to be a genetics counselor, but having exposure to the operating room and seeing how the hospital runs and especially after the conference, I think genetics isn’t for me. But that’s good, it helped me iron that out. I’ve always liked the idea of becoming a physician. I want to attend medical school. The good thing is, the people at Department of Indigenous Cancer Health have welcomed me back with arms opened. This summer kind of ignited a flame in my studying.”

Their work was inspiration to their mentors as well.

“They all represented with respect, kindness, and brought Indigenous perspectives to western science. They are the future for the Mohawks and Haudenosaunee and we could not have asked for a better cohort of brilliant minds to join us for the first summer in our team effort with the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe/Roswell Park NIH Native American Research Centers for Health collaboration,” Dr. Haring says.