The littlest cancer fighters need special nurses.

The six pediatric nurses at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center are often called upon to do more than other specialties: They need to help children, some too young to talk or understand what’s happening, through a scary and difficult time, while also comforting and supporting their parents and caregivers.

The nursing team includes Anita McCabe, RN, AAS; Angelica Zachara, RN, BSN, CPHON, OCN; Kim Seabolt, RN, BSN, MS, AAS; Michele Leonard, RN, AAS; Sarah Gerard, RN, BSN, and Jenna Lyon, RN, BSN.

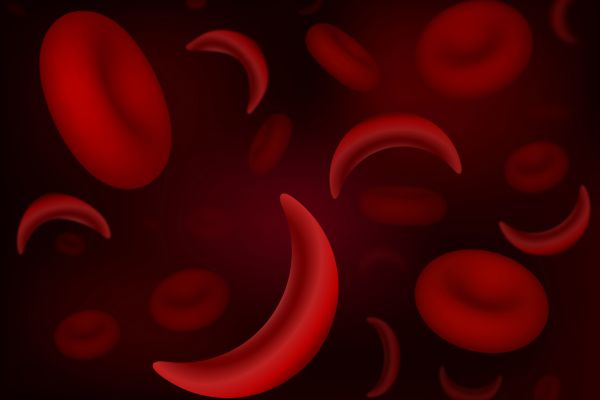

The youngest patient in the care of the pediatric team was two weeks old, says Rose Kumpf, RN, BSN, the Clinical Nurse Manager in Roswell Park’s Pediatric Department. Some of these patients are not being treated for cancer but other conditions, including hematologic disorders like sickle cell disease, or neutropenia. As a result, some patients will only need to spend a few visits with the pediatric nurses; others will remain in their care for longer.

Pediatric nurses also are charged with some tasks other nurses aren’t because of the age of their patients. “It’s more learning of growth and development of the child in certain stages. Everything is within our clinic: We have child psychology, social work. We have a Child Life Specialist, Emily Capron, who is a cancer survivor. Instead of just talking about things, she’s lived it. When she’s working with the patients and teaching about port placement or going through chemotherapy, she’s done it. She knows what and how to do it. We also have phlebotomy within our clinic, patient registration. It’s all-encompassing,” Kumpf says.

Pediatric nurses must also receive additional training as part of their education, including a chemo-biotherapy class for chemotherapy administration and can choose to pursue additional certification, such as pediatric hematology oncology. “Our goal is to have our staff 100% certified and three of us are now,” Kumpf says.

Due to the nature of their care and needs, there are a few patients who were diagnosed with cancer as children and continue to see Denise Rokitka, MD, MPH, Director of Pediatric and Adolescent Cancer Survivorship and the Young Adult Program and Oncofertility Program. Most patients would age out when they turn 19, Kumpf says.

The strong relationships built between nurses and patients and their families is evident, as some care providers will give parents their personal phone numbers in order to stay in touch during and after treatment.

“Our oncology kids are here frequently, as are the kids who need regular transfusions. They’re here every three to four weeks,” allowing those relationships to grow quickly, she says.

The nursing staff also works closely with the Visiting Nurse Association, a group that provides at-home care for patients, and they will work together on preparing blood draws for testing to make the child’s visit a little faster with a little less waiting involved.

Never miss another Cancer Talk blog!

Sign up to receive our weekly Cancer Talk e-newsletter.

Sign up!Getting to know each child well helps to ease stress

Pediatric nurses also have to be aware and prepared for when their patients are already stressed out before their appointment even begins. There are iPads in the chemotherapy infusion bays and big TVs in other rooms to help keep them entertained and distracted during treatment, in addition to a playroom and a dedicated artist to work with the children when they have time. Over time, pediatric nurses learn which methods best calm an individual child’s anxiety or how to manipulate their ports or other sensitive areas. They also learn how best to share information with the patient, in addition to their parents or caregivers.

“If the kid learns to trust the nurse, they’ll be more relaxed, and their parents will be more relaxed. If the parent knows the nurse well, they’ll be more relaxed and their child will be more relaxed too,” Kumpf says. Given the partnership between Roswell Park and Oishei Children’s Hospital, nurses from the two hospitals often will share notes on their patients to help keep things as stress-free as possible.

“It can be little things that are important, like whether a nurse will use the ‘freezy’ spray on a child or whether they have a problem with the wound dressing and it’s better to use paper tape and gauze,” she says. “Sometimes children will get nauseous when their port is being flushed. That doesn’t happen to adults. Sometimes a child can feel a cool sensation when that happens, or sometimes they can taste or smell it. We had a patient who reacted badly to some medication and now we use an injection, but now he basically has post-traumatic stress about it and he’s not a happy camper. When we know this, we can prepare for it.”