This is the second in a series of three articles about the rising number of cancers caused by overweight or obesity. Missed the first part? Find it here.

Today most adults in the United States are overweight or obese. The majority of those people are obese, with a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 30 or higher.

Excess weight increases the risk of developing cancer and can also raise serious challenges after a cancer diagnosis. The National Cancer Institute warns that obesity "may worsen several aspects of cancer survivorship, including quality of life, cancer recurrence, cancer progression and prognosis."

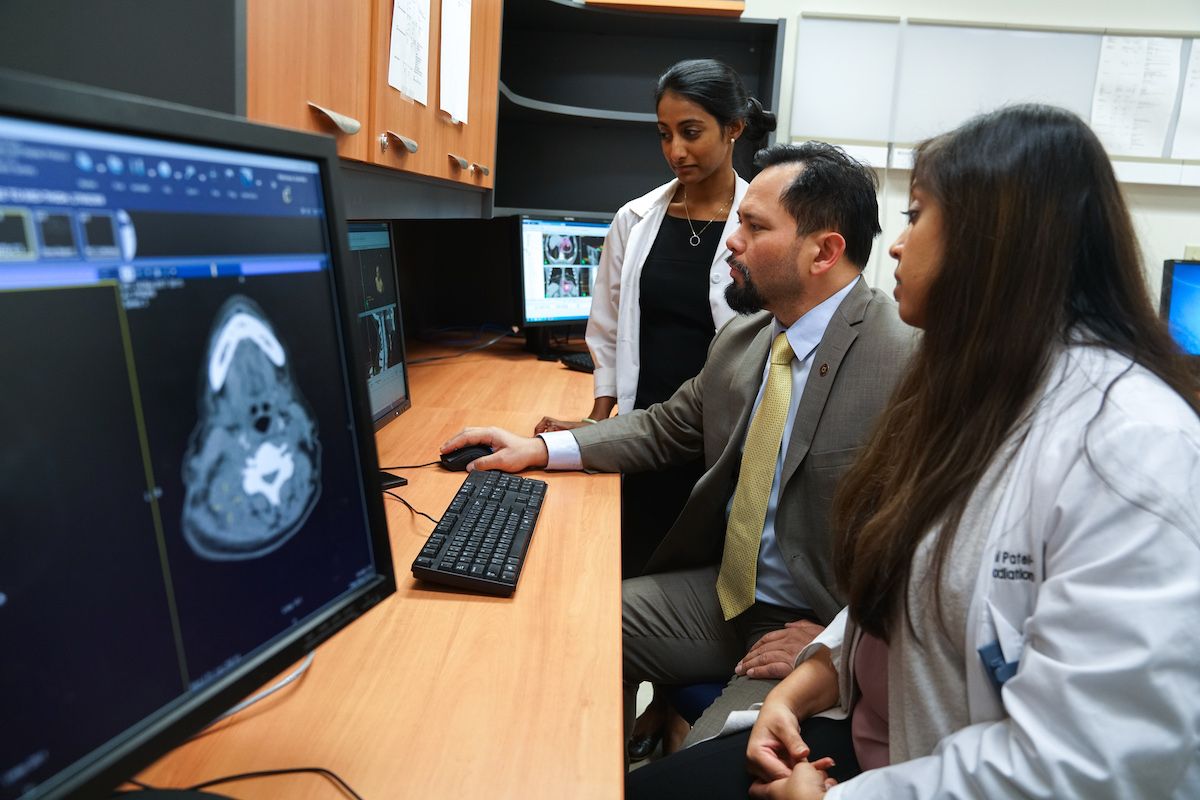

We asked some of our experts to describe the difficulties that can arise for obese patients during cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Medical Imaging

Medical imaging is used both to diagnose cancer and to provide critical information about the tumor in order to plan safe, effective treatment. Benjamin McGreevy, MD, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, says CT scans, x-ray and fluoroscopy are the main methods of cancer imaging, but ultrasound, MRI and nuclear medicine are used as well.

Weight limits of the equipment can be one of the first obstacles in imaging obese patients. While most MRI and CT tables can support 450 or 500 pounds, the patient's body must still fit inside the cylinder of the machine, and sometimes it doesn't. David Mattson, Jr., MD, Department of Radiation Medicine, says that in those cases, "I have to plan the treatment using techniques we used before we had CT scans, which are less precise. There are limited options for treating those patients."

McGreevy adds that even when obese patients are able to fit inside the imaging equipment, images produced by MRI may be grainy or blurry, obscuring important details. In the same way, fat can hide critical diagnostic information during ultrasound, which creates images using echoes from sound waves transmitted through the patient's body.

A similar problem occurs with x-ray, fluoroscopy, and PET scans, which create an image by transmitting photons through the patient. In larger patients, the body mass can slow down the photons' energy, leading to fuzzy images.

Although "we've developed ways around these problems, it's still a concern when we're making a diagnosis," says McGreevy.

Anesthesia

"A couple of things really concern us about obese patients," says Kathleen O'Leary, MD, Chief of Surgical Anesthesia. "Number one is the patient's airway and our ability to safely deliver oxygen to them.

"Fat can obstruct the upper airway. When they relax and go to sleep — either regular sleep or under general anesthesia — the extra tissue in the back of their mouth and above their larynx collapses and makes it difficult for air to get in and out. That restricts our ability to ventilate them well.

"There's a very high rate of obstructive sleep apnea in obese people," she adds. Over time, this condition — which is often signaled by heavy snoring — can lead to serious health consequences. It carries additional risk for someone undergoing general anesthesia. Because some patients may not know they have obstructive sleep apnea, O'Leary and her colleagues use a screening tool called STOP-BANG to identify those at risk.

"Many obese patients also have other diseases that put them at high risk for anesthesia," O'Leary adds. "They may have heart disease due to the stress on their heart of circulating blood to all the extra tissue; high blood pressure; diabetes; and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)." GERD increases the chance that anything in the stomach might move up into the airway — and possibly be inhaled into the lungs — while the patient is going under or waking up from general anesthesia, or during deep sedation.

O'Leary says Roswell Park's High Risk Committee reviews the most challenging surgical cases, many involving obese patients, to weigh the risk of general anesthesia against the risk of not performing the surgery. Committee members carefully evaluate all the treatment options the patient would have if surgery could not be performed. They also consider all other medical conditions the patient has. If the risk of general anesthesia is too great, the obese patient may not be eligible for surgery.

"We routinely care for patients with all levels of obesity," says O'Leary, "and for those who have higher risks for treatment, we proceed only after careful evaluation and discussion among members of our multidisciplinary team."

Surgery

Removing the tumor — and, if necessary, the nearby lymph nodes — can be difficult in obese patients, says Steven Hochwald, MD, MBA, formerly of Roswell Park.

"We prefer to use a minimally invasive approach for many cancers, including many GI cancers," he explains, "but it can be more difficult in obese patients, because there's less room to maneuver and more difficulty visualizing critical structures. In order to see and expose the tumor, often we have to make bigger incisions. That means greater risk of infection and problems with wound healing." If the patient also has diabetes, a condition common in obese patients, there is added concern about both of those risks.

In addition, obese patients may have trouble walking, and if they are unable to move around much after surgery, they will face a higher chance of developing potentially fatal blood clots as well as a higher risk of pneumonia.

If the risks are too high, the obese patient will not be eligible for surgery.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation beams must hit the tumor precisely in order to be effective and avoid damaging healthy tissue. That goal is much more challenging if the patient is obese, says David Mattson, Jr., MD, Department of Radiation Medicine.

After medical imaging pinpoints the tumor, the patient's skin is marked to show the location of the target. The markings stay in place while the patient receives daily treatments, usually over a course of several weeks. "But when patients are obese, the skin moves around a lot, so those marks can move to the left or right. Even millimeters make a difference, which means the setup is less reliable."

In such cases, the Radiation Medicine team can use on-board imaging (OBI) technology, which combines a CT scanner and the radiation equipment, enabling the team to take a CT scan immediately before treatment to confirm the correct positioning of the body. "That's one of the things we rely on to optimize treatment for these patients," says Mattson.

But it's harder to overcome other difficulties. "The larger the patient is, the deeper we have to push the radiation, because there's more distance between the tumor and the skin surface. We need to use more radiation to do that." More radiation means that healthy areas of the body are more exposed to it, "and unfortunately, we see a lot of toxicity in those situations." Radiation dermatitis, a result of toxicity, often occurs in places where excess skin folds over on itself, because the area at the bottom of the fold tends to receive a large dose of radiation.

"If the skin dose is too high, we may have to use intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT)," adds Mattson. "That's a more involved setup, but it's safe enough that it doesn't give too great a dose to the patient's skin."

Never miss another Cancer Talk blog!

Sign up to receive our monthly Cancer Talk e-newsletter.

Chemotherapy

Up until 2011, it was often difficult for pharmacists to determine the dose of chemotherapy required for overweight or obese patients, says Grazyna Riebandt, PharmD, BCOP, Clinical Pharmacy Service Director. There were significant concerns that treating a larger person by increasing the dose used for normal-weight patients would also increase toxicity. But limiting the dose meant the patient's cancer might not be treated effectively.

Then the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) conducted an extensive review of published studies about chemotherapy dosing for obese or overweight patients. Based on data from those studies, in 2011 ASCO published guidelines advising that, unless there are complicating factors, "we use actual body weight for the patient, regardless of their weight, to determine the correct dose," Riebandt explains.

ASCO concluded that dosing according to body weight is not only safe but also very important to ensure that the drugs will work against the cancer cells. Says Riebandt, "We do not ever want to compromise the efficacy of the treatment, but patient safety is always our priority."

Obese After Diagnosis? Now What?

If you are obese and have already received a cancer diagnosis, your Roswell Park team can help you determine the best course of action. Do not attempt to lose weight without consulting your physicians. And be sure to check out the ASCO guide "Managing Your Weight After a Cancer Diagnosis."

Remember that Roswell Park patients have access to the guidance of dietitians who specialize in nutrition for cancer patients. Ask your Roswell Park team for a referral to Clinical Nutrition.

Part 3 of this series will look at the main factors driving the obesity epidemic and talk about habits you can change to reduce your risk for weight-related cancers.

Stay tuned to Cancer Talk.