Jim Sniadecki is an avid supporter of the Ride for Roswell, participating in it for more than 10 years and consistently raising enough funds to be part of the Peloton event featuring the top fundraisers.

When he started, he did it out of belief in the cause and wanting to support Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, where his wife, Karen Sniadecki, has been a department administrator for some time. Jim didn’t have a family history of cancer, but he and some friends got a team together and raised $275.

He was in his second year of participating in the Ride when a visit to a family practitioner brought up something unusual.

“He said ‘You’re in great shape except your nipple’s a little inverted. I want you to go for a mammogram,’” Jim recalls. “I go home and tell my wife and she couldn’t see anything. So we got in here to Roswell Park, we got the mammogram, and three days later, the day before the Ride, they tell me I have stage 2 breast cancer.”

The next morning, Jim woke up and participated in the Ride.

Two weeks later he had a radical mastectomy and four lymph nodes removed, then went through eight cycles of chemotherapy and 30 doses of radiation. He lost all his hair and is now on a regular dose of tamoxifen, an estrogen-blocking medication, to help prevent a recurrence of the cancer.

Today Jim is back to his regular self, even using his 70th birthday party last year as a $4,000 fundraiser for the Ride. But he has changed in one big way since his diagnosis: He’s become a strong advocate for helping men understand that they, too, can get breast cancer. “I tell a lot of my friends. I’ll do a post on Facebook and say this is what to look for. So far, five people I know have gone with my advice and were diagnosed. They all had earlier stages than me,” he says.

Many types of breast cancer are linked with genetic markers or mutations so Jim and his daughters were tested to see if his breast cancer might have a genetic factor. All of the marker tests came back negative, he says, describing his diagnosis as “a fluke.”

“It could have been caused by something environmental, but it might have been a gene gone wild. I have a big, big family and that genetic testing covered everybody with parts of your genome,” he says. “It helped everyone to know. I had to do it for my kids, for my sisters and cousins and their kids.”

Prior to his diagnosis, Jim had no pain, swelling, discomfort or other indication that might have suggested something was wrong. He credits his family doctor, who he describes as “an old-school Hippie type,” for noticing the small abnormality and recommending the mammogram — a screening test Jim continues to receive every year as part of his monitoring and survivorship care.

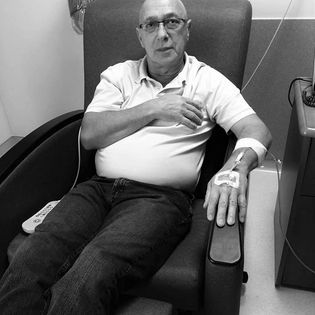

Still, even among friends who have known him for years, his diagnosis was hard to grasp. “People have said, ‘You’re full of crap’ when I try to tell them that men get breast cancer too. I have a picture with a scar that I show them. And I have one of me sitting there doing chemo. Then they usually say ‘Oh, I’m sorry,’” he says. “When I was first diagnosed, I told my immediate family, my daughters. I told my sister, who I’m close with, and I told my mother-in-law. That’s it. During treatment, we took a trip to Myrtle Beach and people were asking why I was bald.”

The man in the women’s club

October is awash with pink, reminding women to get their mammograms and the importance of early detection when it comes to finding breast cancer early, in its most treatable stage. Very little is said in campaigns about the risk of male breast cancer, because it is diagnosed at a significantly lower rate than in women.

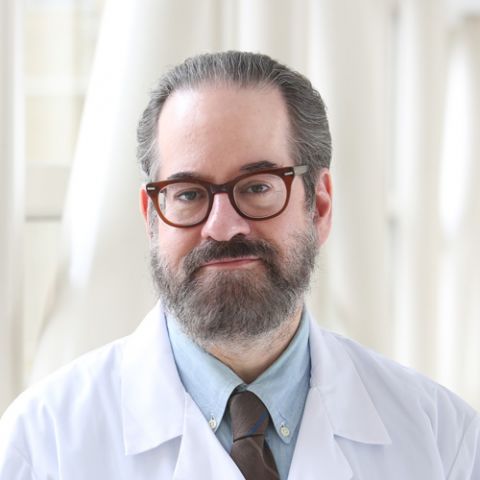

“We see about 20 new male breast cancer patients a year,” confirms Ellis Levine, MD, Chief of Breast Medicine at Roswell Park. That number represents about a small fraction, in the single digits, of all new breast cancer patients at Roswell Park annually.

Breast cancer research and treatment is based on what works best in women, but is exactly the same care provided for men, Dr. Levine says.

“What is different is that men tend to be more commonly hormone-receptor positive than women. They tend to present at a later age and have more comorbidities because they’re diagnosed when they’re older. All of our information about how to treat men with breast cancer is extrapolated from treating women. There are just not enough men with breast cancer to practically perform clinical trials in order to figure out what works best for them,” he explains. “When we treat men with breast cancer the same way we treat women with breast cancer, they do very well.”

Dr. Levine acknowledges that many men might be unaware that they can develop breast cancer because other cancers pose a higher risk to men, including prostate and colorectal cancers. He also credits and applauds Jim for being such a strong advocate for helping educate those he can about the reality of male breast cancer.

“For every Jim, there are 50 people out there with male breast cancer who don’t want to be heard from after treatment,” Dr. Levin says. “I think the reason men don’t talk about it is because people might not believe them. If you get that reaction, what’s the point? You feel somewhat demoralized because people don’t believe you. The men who really need to know about it are those who have had a family member, a mother or sister, or especially a father, who had the disease because it can be passed down. Even though their statistical risk would be much lower than a woman in the same family, it’s still a risk.”

“Cancer/vivor”

Jim says he’s more compassionate after going through treatment, but misses the mustache he says used to rival Tom Selleck’s iconic crumb-catcher. He and his wife have changed their diet a bit in the past few years, but overall, he’s the same guy cracking jokes about his cancer while reminding his friends to take his story seriously.

He’s also quick to correct someone who calls him a survivor, however. He prefers “cancer/vivor,” a term he coined. “You survive an accident. You beat a disease,” he says. “I never said I’m a survivor. I beat the disease.”

Editor’s Note: Cancer patient outcomes and experiences may vary, even for those with the same type of cancer. An individual patient’s story should not be used as a prediction of how another patient will respond to treatment. Roswell Park is transparent about the survival rates of our patients as compared to national standards, and provides this information, when available, within the cancer type sections of this website.