Going through cancer treatment can be an overwhelming, confusing process. Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center offers patient navigators specifically for patients from Indigenous and rural communities to help make the journey a little less difficult.

What is special about this navigation program is that it is based on the Two Row Wampum belt agreement. The Two Row is an agreement between the Haudenosaunee and the Dutch to ride down the river of life in parallel with each other in separate vessels; repeating each other’s cultures and beliefs. This translates into our navigation program with having to arms — indigenous and rural. Each operates differently with the same goal in mind.

A team of patient navigators are provided through the Department of Indigenous Cancer Health, where research is translated into community-based services. Three of these navigators are assigned to work with Indigenous communities across Western New York. But instead of working directly and automatically with patients, the navigators start by meeting with their tribal leadership and government in order to help foster trust and build a relationship with a community that has historically been underserved when it comes to healthcare. The positions are funded through a grant from the Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation.

“We partner with organizations outside the nation or even different departments within each nation in order to do outreach on each territory,” explains Whitney Ann Henry, coordinator for the navigators. “Wherever our community gathers, that’s where we want our navigators to be.”

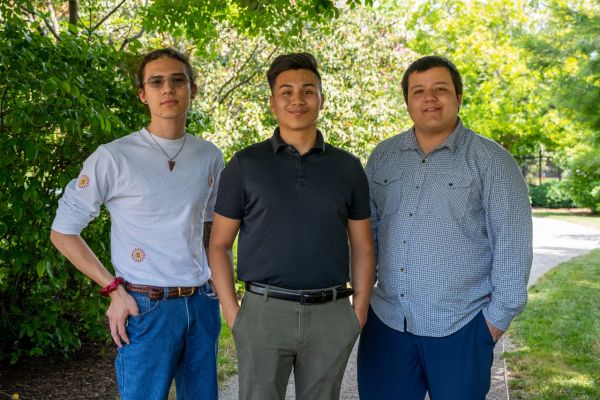

Nancy Washburn (Mohawk) is responsible for working with offices in Niagara County, including the Tuscarora and Tonawanda tribal lands; Marissa Haring (Seneca) is responsible for the Seneca nation in Cattaraugus, Erie and Chautauqua counties and David Silverheels (Seneca) works with the Allegany territory in Salamanca, through collaboration with area not-for-profits, grassroots organizations and a federally qualified health center. Each one is a member of the community they serve, an important factor when it comes to building those relationships with tribal leaders.

In addition, Roswell Park has two rural navigators, Chelsea Redeye (Walker River Paiute) and Rena Phearsdorf (Seneca), who work in federally qualified health centers, meaning they can have direct contact with patients and access to their medical information, thereby making them able to recommend screenings and other early detection practices, all without having to wait until a patient reaches out for assistance.

“There’s a lot of mistrust and historical trauma in our community,” Henry says. “They’re hesitant to come to Roswell Park and any medical center. Our navigators help a lot with that. That makes a huge difference. That’s a reason why we chose who we did as our navigators. They were a good fit for that area.”

That mistrust of medical institutions means many people who come to community events at which the navigators are present have already been diagnosed with cancer. “They’re already at Roswell Park and are looking for additional support or help, or they’re not understanding what the doctors are saying, so our navigators are another helping hand,” Henry says.

Building relationships with leaders

Unlike other patient navigators, who have established relationships with hospitals and can directly contact patients and access their medical charts for proactive reminders about screenings, navigators must be invited into events and offices on Indigenous lands. They’re building relationships with community organizations, like the Indian Health Services (IHS) office in Lockport and the JC Seneca Foundation in the Southern Tier, to establish their presence and help put patients at ease with Roswell Park.

“The IHS office is working on building their clientele. They offer dental and behavioral health services. They’re also at a point where they’re trying to be able to invite people to check out their facility and Nancy works with them a lot,” Henry says. “They’re another resource for healthcare. A lot of my community members in the Tuscarora nation, and an increasing number from Tonawanda Seneca, they’ll use IHS for the dentist. We do a lot of outreach events with IHS and with Native American Community Services.”

Despite the additional steps needed to gain access to patients, Henry says patients are able to reach out to navigators if they’d like assistance. There’s also the option of utilizing a virtual-navigation program to help get the process started by calling 1-888-RPGUIDE. “That allows other members who aren’t local to call in, take a health assessment and, if they have specific questions or want to get in touch with a navigator, they can call that number and get in touch or short-term navigation with screening. It’s another way for us to help our relatives.”

Learn more about the Department of Indigenous Cancer Health

The Department of Indigenous Cancer Health) fuses multidisciplinary expertise and generational knowledge to create a culturally-attuned continuum of cancer care for our Indigenous communities — from prevention through survivorship.

Taking care of relatives

Taking care of relatives fits into the navigators’ work very closely, as family relationships are central for Indigenous communities. It also underscores why it’s important for cancer education outreach efforts to be a big part of the navigators’ work. “We have to take care of ourselves in order to take care of the rest of our family. If we’re not healthy, how can we be there for them? It’s not just for you but you have to be there for your grandkids. We think about seven generations – is this going to help my grandkids’ grandkids down the road. That’s a lot of what we base our work on,” as knowing a family’s history of cancer can help direct people to early detection and screening services like those offered by Roswell Park, Henry says.

In the future, the Navigator program hopes to have a presence at Roswell Park, so someone from one of the tribal communities could meet with someone “who looks like them” when they arrive at the main hospital for treatment. Another goal is to be fully integrated into each nation’s healthcare centers while still being present and conducting community outreach during bigger events, like the socials and powwows Henry and her team attended this past summer.

“I’m from the Tuscarora Nation and this summer they had their first field days since the pandemic. I reached out to the woman in charge of vendors and asked if we could set up a table, explaining we would provide information on the program,” Henry says. “They put me right under the tent with the rest of the nation’s programs. That was a huge step for us! A lot of people will come back who don’t reside on the territory or they’ve moved out of state, but they’ll come back for these events. It was good to see members that I haven’t seen in years, to give them some education on our programs and screening opportunities. We take those invites and we’re so happy. That’s a big deal.”

As a navigator, Silverheels knows he’s providing an important service to his community. “I hope to empower all those I encounter to make informed choices and receive timely care. As we know, Western New York is filled with many unique cultures, one being the Indigenous population. Health disparities within Indigenous populations in the U.S. are significant and numerous…The importance of having Indigenous patient navigators who are very familiar with Indigenous culture and customs and their respective federally or tribally managed healthcare systems goes a long way in building trust and rapport sooner. Being seen as familiar faces in the Indigenous communities we serve and being consistent in our messaging will definitely strengthen our relationships and lead to better health outcomes.”

Navigation is “one of the most effective ways to educate people on cancer prevention and encourage them to get screened for cancer,” Haring adds. “As navigators, we are trusted sources of information and make people more comfortable to talk about cancer. We can also make the screening process more understandable and accessible by helping remove barriers such as insurance and transportation. This job is so important to me because I get to work in the community where I am from.”