Take it from George Grace: if you’ve smoked your entire life, you listen closely to news about innovative cancer treatments.

Grace listened, even before a spot on his lung led to a diagnosis of early-stage non-small cell lung cancer.

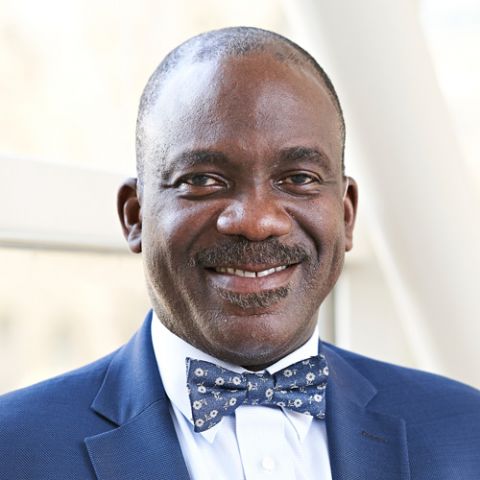

So last April when he sat down to discuss treatment options with Chumy Nwogu, MD, PhD, FACS, Department of Thoracic Surgery at Roswell Park, his brain raced ahead of the surgeon’s words. Nwogu explained that part of a lung would have to be removed, “and we have another treatment where, in addition to the surgery, we expose the cells to intense light and —”

“Photodynamic therapy!” Grace called out. He already knew about the treatment — called “PDT” for short — because “I had paid attention. And it’s very interesting stuff.”

That’s how he became one of the first patients to enroll in a clinical trial that delivers PDT directly to the lung during surgery, with the goal of wiping out any cancer cells left behind. The phase I trial is studying the side effects of the treatment and trying to zero in on the highest and safest dose of light.

What is PDT?

Developed at Roswell Park in the early 1970s, PDT begins when the patient receives an injection of a drug called a photosensitizer. Something remarkable happens when cells that have absorbed it are exposed to laser light: a reaction kills the cells and shuts down blood vessels in the tissue surrounding the tumor (called the margin). Several studies suggest that it may also stimulate the immune system to track down and kill cancer cells throughout the body.

Following treatment, the patient has a strong sensitivity to visible light and must take precautions to avoid sunburn. Depending on the type of photosensitizer (PDT drug) used, this can last anywhere from a few days to 12 weeks.

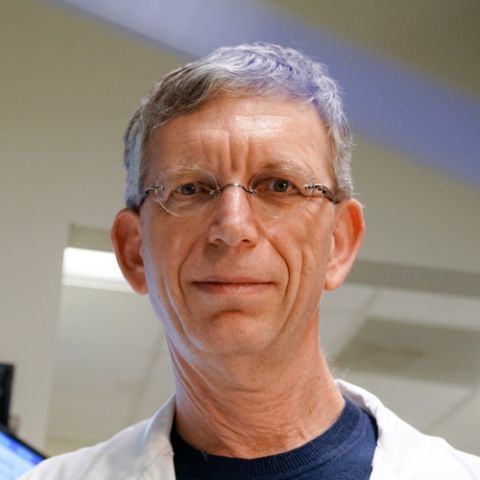

Gal Shafirstein, DSc, Director of PDT Clinical Research, Professor of Oncology and member of the Cell Stress Biology Department at Roswell Park, points out that PDT treatment is intended to improve the cure rate for cancer. It can be used as a single therapy or added before, during or after standard-of-care therapies are given, with the aim of improving outcomes.

Never miss another Cancer Talk blog!

Sign up to receive our monthly Cancer Talk e-newsletter.

What’s new about this way of delivering PDT?

PDT is FDA-approved for treating several types of cancer, including “very early-stage or late-stage lung cancer,” says Nwogu, who is principal investigator of the clinical trial. “It’s a promising tool to decrease cancer recurrence and improve long-term outcomes.”

Usually PDT is given immediately before or after surgery, but until now, delivering the treatment during lung surgery had been done mainly for treating malignant mesothelioma. “PDT is not used for this particular purpose or in this particular way for lung cancer,” Nwogu explains. “As far as we know, we are the only ones who have done it.”

Nwogu adds that the new procedure relies on special tools developed by Shafirstein that are designed to “assess the quantity of light energy being delivered in various areas of the chest,” for greater precision. While Nwogu performs the surgery, Shafirstein is on hand in the operating room to advise the clinical team members as they deliver the PDT.

Patient perspective

What’s the treatment like from the patient’s point of view? The day before the surgery, George Grace headed to Roswell Park for an injection of the photosensitizer, which “felt like a blowtorch on my arm,” he says candidly. He was “extremely thirsty” when he woke up after the surgery, “but I didn’t have much pain."

Although he didn’t feel sensitive to light, he followed the instructions he had been given before leaving the Roswell Park hospital, protecting every inch of skin to avoid sunburn and wearing wraparound sunglasses. He and his wife, Donna, also had to cover the windows of their house in dark wrapping paper for 15 days. “But I felt pretty comfortable,” he recalls.

Six months later, in October of 2016, medical imaging and a biopsy of Grace’s lymph nodes showed no signs that the cancer had spread. Today the temporary light sensitivity is gone, and he has not experienced any other side effects. He walks and rides a bike. A prolific artist, he also continues to paint.

“It’s really great,” he says. “Bless you guys! We’re so lucky to have Roswell Park here.”

Editor’s Note: Cancer patient outcomes and experiences may vary, even for those with the same type of cancer. An individual patient’s story should not be used as a prediction of how another patient will respond to treatment. Roswell Park is transparent about the survival rates of our patients as compared to national standards, and provides this information, when available, within the cancer type sections of this website.