Elizabeth Griffiths, MD, Director of Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) in the Department of Medicine at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, never wondered which career path she would take.

“I always knew I wanted to be a doctor,” she says.

And with a mother who is a primary care physician, Dr. Griffiths began on-the-job training early.

“My mother specialized in taking care of older patients. As a young person, I had the opportunity to shadow her in clinic and on her rounds more often than I can remember,” she recalls. “She always sat with people and made them feel heard. I have tried to emulate her bedside manner.”

But when she told her mother she wanted to be a doctor, her mother was hesitant.

“She worried that it would be an all-encompassing choice,” Dr. Griffiths says. “Ultimately, she and I discussed how being a physician is a calling. Not everyone has the drive to do the work and provide care, but for those of us who do, it can be an incredibly fulfilling life choice.”

During her university years, Dr. Griffiths got her first glimpse of her future specialty when a close friend died of leukemia.

“It was a shocking experience to have an 18-year-old who seemed entirely fine one day die of overwhelming infection the next,” she recalls.

Rotation reverses planned specialty

She graduated from the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill School of Medicine in 2002 as a Doctor of Medicine with Distinction. She planned to specialize in infectious diseases and as an intern at Johns Hopkins Hospital, she applied to short-track into an infectious disease fellowship program.

“But during the match, I completed my rotation on the inpatient leukemia service and fell in love with the care of patients with acute leukemia,” she says, and adds what makes such care special.

“I can still practice extensive management of infectious diseases, I get to make the diagnosis at the bedside by review of the blood smear, and I also get to partner with patients directly in choosing the treatments that are right for them,” she says. “Because leukemia is a disease of the blood, the distance between questions explored with bench science and those at the bedside is relatively straightforward to bridge. This combination of features made it clear that caring for and learning about leukemia was the direction for me. I have not looked back since.”

In 2010, Dr. Griffiths joined Roswell Park’s Leukemia Service in the Department of Medicine for a specific reason.

“Roswell Park offered me the opportunity to pursue laboratory research in a place with a uniquely fantastic commitment to procurement of viable patient samples,” she says.

“One of the issues I had in my prior work was difficulty with analysis of improperly prepared or stored samples. Samples from the Roswell Park Hematological Procurement shared resource are unparalleled in the world for quality. Almost all the work I have been able to do stems from this resource as a support to understanding the impact of various cancer treatments on leukemia and MDS cells from patients. The ability to use primary patient samples of excellent quality to do real experiments has been central to the success of my research.”

When asked what interests her more about her work – being a clinician or a researcher – Dr. Griffiths answers that both do.

“I can’t separate my clinical work from my research. And doing both offers me a real advantage. From my perspective, these are one and the same. In order to offer my patients the best and most advanced treatments, I have to be part of research and thus a research institution. Only in doing this will we be able to one day cure patients with leukemia.”

Subspecialty helps her offer patients better care

She appreciates that at Roswell Park, physicians are able to “also become subspecialized,” something that makes them stand out from other oncologists working with blood disorders, and also helps them better treat those unique patients.

“Each of us has a particular research focus and we get to become distinctive experts in that focus. I am interested in MDS, acute leukemia and early-phase clinical trials,” she says. “Because I get the luxury of focusing relatively narrowly, I can offer patients an exceptional perspective.”

She also marvels at how leukemia treatments have changed in the past few years, evolving as research zeroes in on more effective approaches.

“More than eight new drugs have been approved for leukemia in the last 10 years,” she says. “Some of these drugs are based upon an improved understanding of the function of the immune system as an effective treatment for cancer.”

Never miss another Cancer Talk blog!

Sign up to receive our monthly Cancer Talk e-newsletter.

Sign up!Lab work seeks to strengthen patients

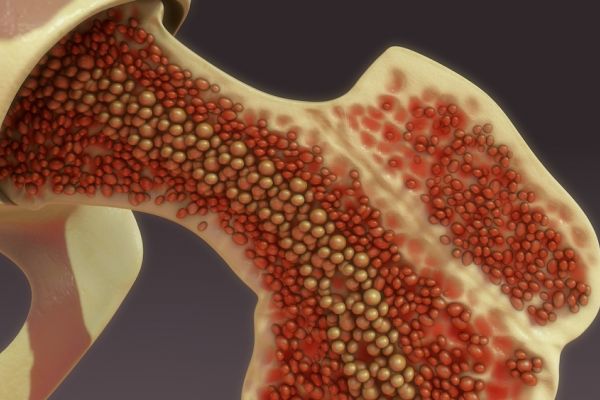

Dr. Griffiths and her laboratory team are a major reason that The MDS Foundation recognizes the Roswell Park MDS program as an MDS Center of Excellence. Her lab continues to explore the role of the immune system in treating patients with MDS and hematological malignancies, and particularly, how bone marrow defects can alter the ability of the immune system to recognize and potentially kill cancer cells in the context of different treatment approaches.

The team’s previous studies showed that hypomethylating drugs, a standard of care for MDS and some patients with acute myeloid leukemia, can activate immune targetable genes that can be seen by compatible T cells. Subsequent clinical trials found that “while MDS patients can mount a low-level immune response against these induced targets, the response is blunted compared to patients with other types of solid cancers.

“We have since shown that patients with MDS seem to have a unique and particular defect in their immune systems which compromises the ability of these patients to mount a good immune response against cancer, partly due to a defect in the production of dendritic cells. These cells are critical to mounting a successful immune response against cancer and seem to be missing in patients with MDS.”

Today, Dr. Griffiths and her team plan to develop ways to give back these cells to those patients, “and in so doing, improve the response to various immune-based treatments for people with AML and MDS.”