Skin cancer is the most common form of cancer worldwide. It is usually caused by excessive exposure to sunlight or other sources of ultraviolet light, such as tanning beds. The rarest but deadliest form of skin cancer is melanoma, which is aggressive and can spread rapidly if not detected and treated early.

Surgery remains the primary treatment for most types of skin cancer, but in cases of advanced-stage melanoma where the tumors have spread beyond the skin to the lymphatic system, bloodstream or other parts of the body, surgery is not effective. Chemotherapy and radiation are generally used in these cases, but many patients do not respond to conventional treatment. In fact, the 5-year survival rate among patients with metastatic melanoma is only 16%.

Newer targeted treatments like immunotherapy have emerged in recent years and appear to be not only more effective than conventional therapy but also better tolerated, because unlike chemotherapy and radiation, these newer approaches are designed to kill cancer cells without damaging healthy ones. As the Director of the Early Phase Clinical Trials Program at Roswell Park, I am responsible for developing novel therapies for many types of cancer, including melanoma. This includes phase I and II trials, where the safety of a particular drug is tested and a therapeutic dose is identified, and phase III trials, where drugs are introduced to patients for the very first time.

MasterKey265 is a combination phase I/III trial that is now open at Roswell Park and 160 other locations throughout the world for patients with advanced melanoma (stage IIIB to IVM1c) who cannot be treated with surgery alone. The study consists of two phases and involves two promising immunotherapy drugs: pembrolizumab and talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC).

Never miss another Cancer Talk blog!

Sign up to receive our monthly Cancer Talk e-newsletter.

Sign up!Pembrolizumab was approved by the FDA in 2014 and is quickly becoming the standard of care for patients with metastatic melanoma. It works by blocking a protein called PD-1 that cancer cells use to suppress the immune response, which allows the immune system to recognize and attack cancer. Although pembrolizumab has proven to be well tolerated and highly effective in shrinking or eliminating tumors, only a small proportion of patients respond to treatment. Those who do not respond to pembrolizumab immunotherapy lack a certain type of immune cell inside their tumor lesions.

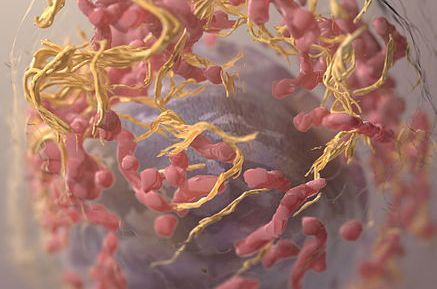

Cancer cells have developed a number of ways to survive, including ways to escape detection and attack by our immune system, but their ability to respond to viral infections is actually quite limited. T-VEC is an oncolytic virus, which is a virus that kills cancer cells, but not healthy ones. I was part of a team that was instrumental in the development of T-VEC, which is genetically engineered from herpesvirus (the virus that causes cold sores). T-VEC acts as a one-two cancer punch, not only killing cancer cells but also stimulating the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. The FDA approved it last year for the treatment of advanced melanoma, and we think it can help overcome the resistance that we’ve seen to pembrolizumab.

In the first phase of MasterKey, T-VEC was injected into the tumors of 21 patients with advanced melanoma, followed by pembrolizumab immunotherapy. This combination was well tolerated and highly effective, with a much higher response rate (62%) than expected with pembrolizumab alone. Remarkably, we found that the majority of tumors shrank by 50% or more with this combination therapy. What is even more impressive is that these responses were seen across all stages of melanoma, including the most advanced stage IV cancers. These results were recently published in the journal Cell and have generated much interest in this combination therapy.

In the second phase of this trial, which is ongoing and aims to recruit 660 patients, pembrolizumab will be given alone or in combination with T-VEC. Patients will receive treatment for up to two years or until their tumors disappear, their cancer progresses, or they can no longer tolerate treatment. Results will be available in the next few years but so far suggest that this combination therapy is both well tolerated and highly effective. If patient responses are similar to those seen in the first phase, then this trial could establish a new standard of care for advanced or metastatic melanoma.