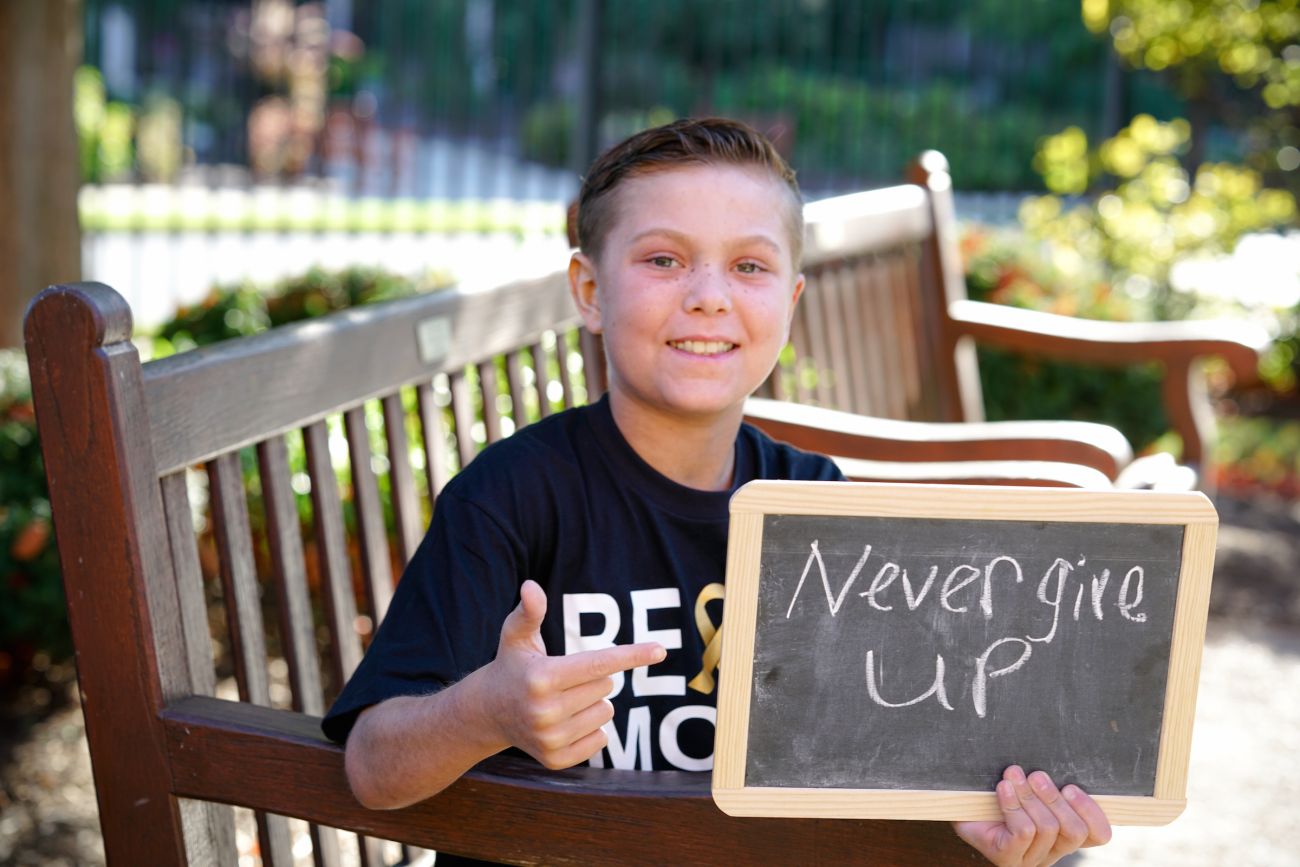

Tips from a Parent of a Pediatric Cancer Survivor

Nobody expects to hear the words “Your child has cancer.” Nobody is prepared. And in our family’s case, our son Emmett was diagnosed with leukemia in an emergency room, and treatment began that day in the ICU. We had no time at all to prepare, or even to comprehend it all at the time.

Never miss another Cancer Talk blog!

Sign up to receive our monthly Cancer Talk e-newsletter.

Sign up!Cancer treatment, especially leukemia treatment and bone marrow transplant, means infusions—too many to count. Aside from chemotherapy, even antibiotics and other medications were infused. It’s been two years since Emmett’s diagnosis, and looking back now, several tactics helped us all cope with the seemingly constant infusions:

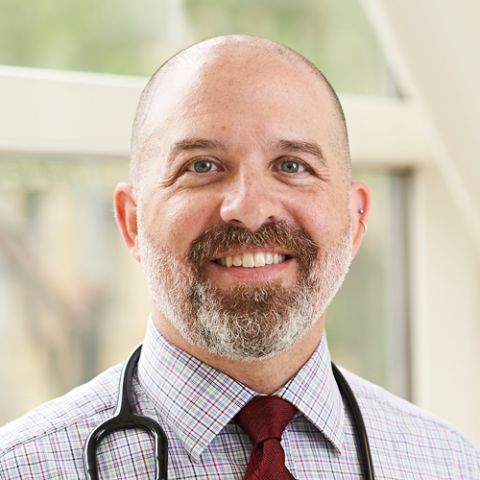

- Have age-appropriate conversations. Our son was 10 years old when he was diagnosed, and he understood what was happening to him. We didn’t try to trick him about anything but talked to him straight, like a little adult. But we struggled at first, and we asked his doctor, Steven Ambrusko, MD, to guide some of the conversations about his disease and the treatment.

- Consult with the child psychologists. These professionals are experts who knew exactly how to talk to our son on his level. He responded really well and opened up to them, and that reduced his anxiety.

- Employ distraction. We used music to help get through treatments. We gave Emmett a Bluetooth speaker so he could play DJ with all his music.

- Bring comforts of home. Even outpatient infusions can take nearly the whole day. We always brought our son’s Sabres blanket, his own sheets and pillow.

- Seek integrated medicine treatments. Pain and nausea were really hard to deal with, but we found the most success with acupuncture, massage therapy and aromatherapy. Emmett was skeptical of acupuncture at first because it involved needle pokes, so I allowed a demonstration on my arm to show him it wouldn’t hurt.

- Get out of the room. (Even if it’s only to the hallway.) Whenever we could, we’d walk the hallways, making laps around the unit. It was during the Olympics, so we set goals: Five laps would earn a gold medal.

- Fuel a passion. Our son loves magic tricks, and allowing him to do them in the hospital helped him connect with others. He performed in the lobby a few times and was asked to visit other patients to entertain them. Making others feel better helped him feel better and remain optimistic.

- Encourage new friendships. Finding others to talk to, through support groups or during treatments, helped both my son and myself. I found comfort talking with other moms in a similar situation. And for Emmett, it didn’t have to be another kid. Few kids have transplants, so he struck up a friendship with a 35-year-old patient and even sneaked down to the gift shop with his own money to buy a teddy bear to cheer him.

- Stay positive. We took our lead from Emmett on this. He never got down. He accepted that this was what he needed to do to get well and always looked forward with optimism and positive spirit.

- Embrace that dang pole. The IV pole that hung the chemotherapy bags became Emmett’s constant companion, but he didn’t let it keep him in bed. He just learned to push it along, and even named it—although not something that’s appropriate to publish!

Editor’s Note: Cancer patient outcomes and experiences may vary, even for those with the same type of cancer. An individual patient’s story should not be used as a prediction of how another patient will respond to treatment. Roswell Park is transparent about the survival rates of our patients as compared to national standards, and provides this information, when available, within the cancer type sections of this website.