If you or a loved one has been diagnosed with cancer, you might already know the basics of cancer staging — but some things might surprise you.

Staging is a way of describing how much cancer is present in your body and how far it has spread (metastasized) beyond the area where it first began. There are four stages: at stage 1, the cancer has not spread outside the organ where it began; at stage 4, it has spread to distant parts of the body. The information used for staging is gathered from various tests and procedures, such as biopsies, X-rays, CT scans and MRIs.

The most common method of tumor staging combines three pieces of information: the size of the main tumor (T), the number of nearby lymph nodes that contain cancer cells (N), and evidence of metastasis (M) — whether the cancer has spread from its original site. This is called the TNM classification system.

Why Do We Stage Cancers?

Staging is important for three main reasons:

- It can help doctors estimate how aggressive the cancer is, and predict the patient’s chances of survival.

- “Staging also helps identify the best treatment approach for that particular stage of cancer,” explains Amy Early, MD, FACP, Department of Medicine. “A stage 1 breast cancer is typically treated differently from a stage 3 or stage 4 breast cancer.”

- “Staging identifies patients who can be included in clinical trials,” adds Dr. Early. “Almost always that’s someone with a stage 4 cancer.”

4 Things That Might Surprise You

1. The stage assigned to your cancer at the time of diagnosis does not change, even if you later go into remission or the disease grows worse.

If your cancer is identified as stage 2 at the time of diagnosis, it will always be called stage 2. Why? For one thing, referring to the original stage gives researchers a way to track and compare survival rates for patients who were diagnosed at the same stage.

“It also gives us the ability to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments given at a specific stage,” explains Dr. Early. A breast cancer diagnosed at stage 2 that later metastasizes to the lungs may need a different treatment than a cancer that was diagnosed at stage 4, when the disease had already metastasized to the lungs — and the chances of survival may be very different as well.

If a stage 2 breast cancer metastasizes to the lungs, it is called stage 2 breast cancer with lung metastases — not stage 4 breast cancer.

2. Not all cancers are staged, and some are staged differently from others.

For example:

- Leukemia and most other blood cancers are not staged, because at the time of diagnosis, the leukemia cells are already circulating in the blood throughout the whole body. Instead, the disease is described as either active or in remission.

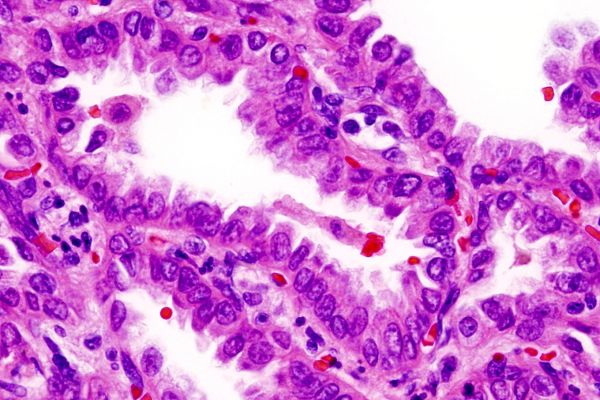

- In the same way, brain tumors are not staged, because while they may spread to other parts of the central nervous system, they rarely spread to organs or lymph nodes in other parts of the body. Instead, the tumor cells are graded from 1 to 4 to describe how different they look from normal cells; grade 4 cells look the most abnormal.

- Small cell lung cancer is usually described simply as either limited stage or extensive disease. “That’s important for making treatment decisions,” explains Dr. Early. “Limited-stage disease means the cancer is confined to the chest. Extensive disease means it’s extended outside the chest, so in that case, our treatment approach will be different.”

3. If you develop a second primary tumor, it is staged separately from your first primary tumor.

“This can lead to some confusion,” Dr. Early acknowledges.

First, it’s important to understand the difference between a metastatic tumor and a primary tumor. A primary tumor begins growing on its own. A metastatic tumor begins when cells break away from a primary tumor and spread to another location. (You could think of a metastatic tumor as the “child” of a primary tumor.)

So when a new tumor develops in someone who already has cancer, pathologists need to examine the tumor cells to find out whether the new tumor is primary or metastatic. This will determine the best way to treat the tumor. “If a woman is diagnosed and treated for a stage 2 breast cancer in the left breast, and five or 10 years later develops a new primary cancer in the right breast, the two are staged separately,” says Dr. Early, “because the new cancer has the same prognosis and treatment options as if there had never been a previous cancer.”

4. Cancer staging continues to change as we learn more about the disease.

The staging system for cancer was first developed in the 1940s. Since then, staging guidelines have been updated every six to eight years based on new information generated by ongoing cancer research.

For example, today staging often includes more information than just T, N and M. Breast cancer staging may note whether or not the tumor has hormone receptors (such as ER positive, PR positive, HR negative), which can guide physicians in choosing the most effective treatments. And lung cancer staging may include information about whether the tumors contain special types of molecules called biomarkers that show whether immunotherapy would be an effective treatment.

“There has been a very meaningful reduction in breast cancer deaths over the last two decades,” notes Dr. Early. “That’s due mostly to the fact that breast cancer is being diagnosed at an earlier stage than it was previously — and that’s just one example of why staging is so important for us. It gives us the ability to evaluate the effectiveness of our treatments by stage, which is critical to the management of a patient with cancer.”

The TNM staging system is managed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), together with the International Union for Cancer Control (UICC). Learn more about cancer staging from the National Cancer Institute and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Never miss another Cancer Talk blog!

Sign up to receive our monthly Cancer Talk e-newsletter.

Sign up!