Learning the difference between chemotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy

Until the 1960s, surgery and radiation were the mainstays of cancer treatment; drugs were not seen as a “cure” for cancer. Apart from hormone therapy for men with prostate cancer in the late 1930s, drug therapies, at best, offered brief, incomplete remission. Then, the National Cancer Act of 1937 provided support for cancer research, setting up the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and doctors and researchers began to pay more attention to using chemical agents and drugs against cancer. The first breakthroughs came in the 1960s and early 1970s, when chemotherapies successfully treated adults with Hodgkin's lymphoma and children with leukemia. Today, more than 600 drugs are approved in the U.S. to treat cancer. Most of these fall into three main categories — chemotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy — and work against cancer in different ways.

Chemotherapy attacks cancer cells

Chemotherapy drugs kill cancer cells by stopping them from growing and multiplying. If the cells can’t grow and multiply, they usually die. Some chemotherapy drugs work during a specific stage of the cell cycle. One of the reasons chemotherapy is given in treatment cycles is to deliver drugs when they will be the most effective. Treatment periods are often alternated with rest periods to allow your body time to get stronger before the next round or “cycle” of chemotherapy.

While chemotherapy drugs effectively attack cancer cells that grow and replicate quickly, chemotherapy drugs also attack some normal healthy cells that grow and replicate quickly, such as blood cells, cells in the hair follicles, and cells in the lining of the digestive tract. This unfortunately is the cause of many of the side effects commonly associated with chemotherapy, such as hair loss, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and low blood-cell counts. These side effects lead to an increased risk of infection, fatigue and bleeding. Fortunately, these rapidly dividing healthy cells are usually able to repair themselves after chemotherapy has ended.

Examples of chemotherapy

- Alkylating agents: Cyclophosphamide, Carmustine, Temozolomide

- Plant alkaloids: Vincristine, Paclitaxel, Vinblastine

- Antitumor antibodies: Rituximab, Trastuzumab, Pembrolizumab

- Antimetabolites: Methotrexate, Cytarabine, Fluorouracil Topoisomerase inhibitors: Etoposide, Irinotecan, Topotecan

Side effects will depend on your health before treatment, your type of cancer, and the type and dose of the drugs. Chemotherapy can cause nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, increased risk for bleeding and infection, hair thinning or loss, mouth sores, constipation, taste changes, loss of appetite, and nerve and skin problems.

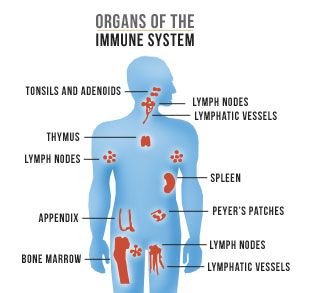

Immunotherapy mounts your defenses

Your immune system involves the many organs and tissues of the lymphatic system and several types of white blood cells. Normally, your immune system attacks foreign or abnormal cells, but cancer cells are sneaky and can “hide” from the immune system to avoid detection. Immunotherapy, also called biotherapy, uses drugs that go after the ability of cancer cells to hide from your immune system. Some immunotherapy drugs mark the cancer cells, allowing the immune system to find and destroy them.

Types of immunotherapies

- Checkpoint inhibitors interfere with how cancer cells avoid an attack by the immune system, rather than targeting the tumor directly. Examples of checkpoint inhibitors include Keytruda® (pembrolizumab) and Opdivo® (nivolumab).

- Adoptive cell therapy aims to boost the natural ability of your T-cells to fight cancer. Your cancer team will take T-cells from your tumor and test them. The T-cells most active against your cancer are grown in a laboratory and multiplied in large numbers, a process that takes two to eight weeks. During this time, you may have chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy to reduce the number of immune cells in your body. After these treatments, the multitudes of laboratory-grown T-cells that are most active against your cancer are given back to you through an intravenous (IV) line to attack the cancer cells. Examples of adaptive cell therapy include Kymriah® (tisagenlecleucel) and Yescarta™ (axicabtagene ciloleucel).

- Monoclonal antibodies are immune system proteins made in a laboratory and designed to attach to specific targets found on cancer cells. Some monoclonal antibodies mark cancer cells so the immune system can detect and attack them. Examples of monoclonal antibodies include Erbitux® (cetuximab) and Herceptin® (trastuzumab).

- Treatment vaccines work against cancer by boosting your immune system’s response to cancer cells. Treatment vaccines are different from the vaccines that help prevent disease. An example of a treatment vaccine is Provenge® (sipuleucel-T).

Side effects of immunotherapy may include skin reactions or problems, flu-like symptoms (aches, fever), diarrhea, fatigue, risk of infection, and inflammation.

Never miss another Cancer Talk blog!

Sign up to receive our weekly Cancer Talk e-newsletter.

Sign up!Targeted therapy blocks cancer growth

This class of drugs works by interfering with certain molecules or “targets” that are key to the cancer cells’ ability to grow and spread. Where chemotherapy drugs aim to kill cancer cells directly, targeted therapies focus on blocking the cancer cells’ growth, with less harm to normal cells. Most targeted therapies are either monoclonal antibodies, which attach to proteins on the outside of the cancer cell, or small molecules, which target specific proteins inside the cancer cells. Researchers continually look for new “targets” on or within the cancer cells for these therapies.

Types of targeted therapies

- Hormone therapies slow or stop the growth of cancers that need those hormones to grow. Examples include Arimidex® (anastrozole) and Lupron® (leuprolide)

- Angiogenesis inhibitors stop the tumor from growing the new blood vessels it needs for continued growth. Examples include Avastin® (bevacizumab) and Zaltrap® (ziv-aflibercept).

- Signal transduction inhibitors block signals from one molecule to another inside a cell, such as the signal for the cell to grow and divide. Examples include Herceptin® (trastuzumab) and Gleevac® (imatinib).

- Apoptosis inducers make cancer cells vulnerable to the normal cell process called apoptosis, which directs old cells to die. Examples include Velcade® (bortezomib) and Lynparza™ (olaparib).

Targeted therapies do have some limitations. The cancer can become resistant, and the drugs no longer have the desired effect. To avoid this, targeted therapies are often given in combination with other cancer drug therapies. Side effects of targeted therapies include diarrhea, high blood pressure, skin rashes, and problems with liver function, wound healing and blood clotting. Drug therapies are part of the treatment plan for many patients to cure cancer, keep the cancer in check, relieve symptoms, and improve the quality of life. If you have questions, please talk to your oncologist or your clinical pharmacist.