In November of 1944, World War II struck a cruel new blow to the German-occupied areas of the Netherlands. In the midst of a brutally cold winter, a German blockade prevented shipments of food and fuel from reaching the region, causing a famine that became known as the Dutch Hunger Winter. By the end of February 1945, the average adult was getting by on fewer than 580 calories per day. Many people resorted to eating grass and tulip bulbs, and an estimated 22,000 people died.

Years later, the tragedy of the Hunger Winter revealed secrets about how our bodies respond to environmental influences even before we’re born. Studies of medical records kept before, during and after the famine showed that babies born to mothers who were pregnant during the famine were more likely than other babies to become overweight and develop diabetes, cardiovascular disease, schizophrenia and other medical problems later in life — even if they were healthy at birth.

And the effects of the famine extended even further. “There were actually altered disease risks in the mother’s grandchildren,” says Joyce Ohm, PhD, Department of Cancer Genetics and Genomics at Roswell Park.

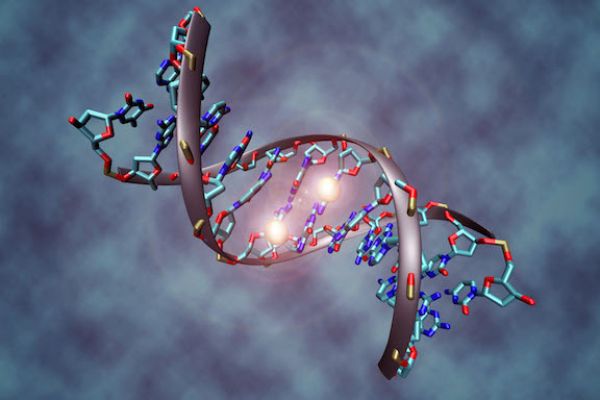

That’s just one example of how our health, including our cancer risk, can be affected by epigenetics. Epigenetics describes how normal genes that control the body’s functions can be switched on or off by different exposures and experiences, from before birth through adulthood.

“A lot of work has been done in environmental epigenetics — studying the effects of things like smoking and drinking and diet and exercise,” explains Dr. Ohm. “This can even include the effects of your social environment, in terms of whether you had a good childhood, your interactions with your parents and siblings, whether you had enough food to eat, and whether you had difficult challenges growing up that may have added stress to your life.”

Never miss another Cancer Talk blog!

Sign up to receive our monthly Cancer Talk e-newsletter.

Sign up!Those changes “can potentially be passed from cell to cell, or from parent to offspring. Epigenetics has a tremendous role in regulating how our bodies ‘talk to’ and interact with the environment.”

For example, our bodies contain tumor suppressor genes, whose job is to prevent cells from turning into cancer. When epigenetic changes cause those genes to switch off, cancer can begin to grow. The same process can affect genes that protect our body from other diseases and even psychological disorders.

The field of epigenetics is relatively new, and researchers are just beginning to understand why genetic switches turn on or off, and how they can be corrected to treat certain conditions. A new epigenetics center, currently in the planning stages at Roswell Park, will bring together scientists from several different disciplines to drive the research forward. Their shared discoveries could result in better ways of preventing, detecting and treating cancer.

In the meantime, says Dr. Ohm, the lesson is clear: “There’s enough data to suggest that healthy lifestyle changes like diet and exercise will affect not only our own health and well-being, but potentially the health of offspring for generations to come. That’s one of the really exciting things about the epigenome. It’s reversible and changeable and adaptable, so the choices we make do have consequences, not only for ourselves but also for our offspring.”