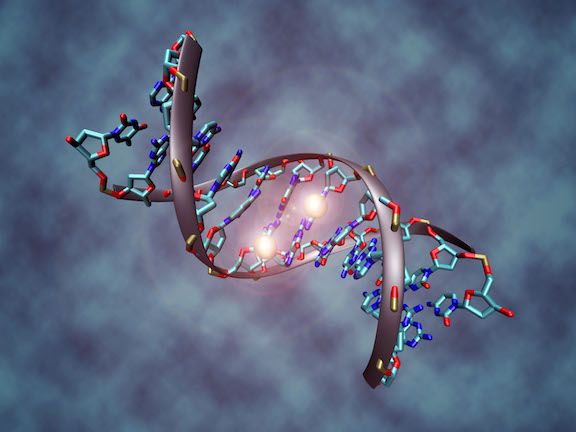

You have about 30,000 genes in your body. Every day they regulate the work of different types of cells to keep things running smoothly — repairing your bones, carrying oxygen throughout your body, fighting bacteria and managing all the processes that make you tick. Most of the time they work the way they’re supposed to.

But sometimes the genes that control cell growth go out of whack, enabling cells to multiply out of control. That’s how cancer begins. Sometimes it happens because of a change (or mutation) in a gene. You might have been born with the mutated gene, or it might have been caused by external influences, such as smoking. Although cancer that is caused by a genetic mutation can be treated, the genetic mutation itself is either permanent or “really hard to fix,” says Joyce Ohm, PhD, Department of Cancer Genetics and Genomics at Roswell Park.

Cancer can also occur when certain normal genes (tumor suppressor genes, for example) are “switched on or off” as a result of environmental epigenetics — influences that occur throughout your life. These may include exposure to pesticides, viral infections, the food you eat, how often you exercise or interactions with other people when you’re growing up. In fact, as you’ll learn in an upcoming article, epigenetic changes may also be triggered by events that happened to your parents, grandparents or even great-grandparents, who passed the faulty on/off switch along to you through your DNA.

But here’s the exciting thing: Unlike genetic mutations, “epigenetic changes can be reversed,” says Dr. Ohm. “The potential for treating not only cancer but other diseases is tremendous.”

Never miss another Cancer Talk blog!

Sign up to receive our monthly Cancer Talk e-newsletter.

Improving treatment response & overcoming resistance

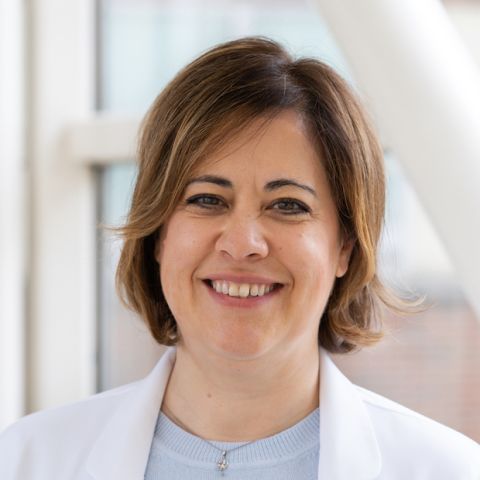

Cancer researchers were some of the first to explore the field of epigenetics, and some drugs have already been developed to correct the on/off switch for some types of cancer. One of those drugs, azacitidine, is already FDA-approved for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome.

Right now the drugs generally aren’t stand-alone cures, but they have an important role to play. “Can we use these just to treat cancer on their own?” asks Dr. Ohm. “Results have been mixed. But these epigenetic drugs have shown some success in improving patients’ response to chemotherapy or immunotherapy, or in overcoming resistance to those standard treatments. That’s probably where the greatest potential is for epigenetics in the immediate future.

“We don’t completely understand yet why one patient will respond to chemotherapy and another one won’t, or why some patients respond to immunotherapies and why some don’t, but we feel we can use their epigenomes to enhance those existing therapies and also overcome resistance for patients who don’t respond to any given standard of care.”

Creating a research powerhouse

She adds that Roswell Park is in the planning stages of establishing a new epigenetics center that will bring together scientists from many areas to create a research powerhouse. “Right now we have several dozen laboratories spread across different departments and research groups for different types of cancer. Multiple labs are looking at how cancer risk is linked to race, gender, environment or environmental exposures, all of which are things that can affect the cancer epigenome.

“We want to get all these scientists talking together. We think a coordinated effort will help move things forward faster and benefit our patients. We want to understand how genetic changes and environmental exposures reprogram your cells and make them more likely to become cancerous.”

New insights into those questions could also lead to more effective ways of preventing cancer in the first place, says Dr. Ohm, who has a special interest in rare soft-tissue sarcomas. “We know that epigenetic changes often take place before we see a genetic change in a cancer cell. If we can see those changes earlier, we might be able to catch a cancer before it really takes hold.”

Dr. Ohm was a little girl when she lost her mother to cancer. That loss continues to drive her forward. “The epigenetics work I do in the lab has the potential to help patients in the immediate future, and that’s fun for me.”

Stay tuned to Cancer Talk to find out how epigenetic changes can be passed along for several generations.