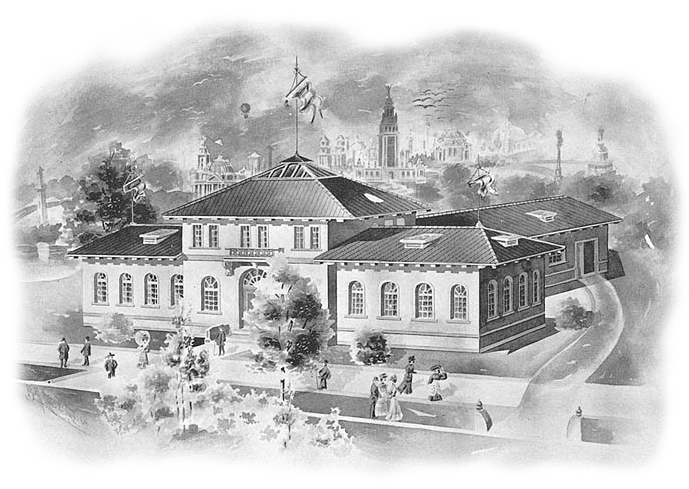

Looking back at the Pan Am Emergency Hospital

Buffalo was the eighth-largest city in the United States when it was selected as the site of the 1901 Pan-American Exposition. The “World’s Fair” was organized to promote commerce and showcase the cultures and achievements of countries in the Western Hemisphere. Set on 350 acres, it promised a spectacle of ornate buildings displaying the latest products and inventions; canals where visitors could glide along in gondolas; animal exhibits, a mirror maze, and performers; gardens; restaurants; and model “villages” inhabited (temporarily, anyway) by people shipped in from far-flung corners of the world.

With a tidal wave of visitors on the way, fair organizers chose one of the city’s leading physicians, Dr. Roswell Park, to serve as Medical Director for the historic event. The responsibility was enormous. Dr. Park directed a team charged with overseeing:

- Food safety, especially the washing and disinfection of water glasses used at drink stands, and the purity of meat, milk, and cream (in an era before electric refrigeration!)

- Sanitation, involving water and sewer lines and 500 toilets located throughout the exhibition grounds

- Urgent medical care for virtually any emergency imaginable

“A most perfect hospital service”

Recognizing the vast range of medical needs that might arise, Dr. Park urged organizers to build an Exposition Hospital (also called the Emergency Hospital) to provide care for visitors and staff. “The fire which occurred in Chicago during the World’s Fair, and various happenings in St. Louis and elsewhere, had profoundly impressed me with this need,” he recalled later.

Similar to a modern-day urgent-care center, the hospital was not meant to be an inpatient facility. In serious cases, patients would be stabilized and then transferred to other hospitals in the area, primarily Buffalo General. That’s why the Emergency Hospital was constructed close to the fair’s Elmwood Avenue gate, allowing easy access for patient transport via the electric ambulance or horse-drawn carriages.

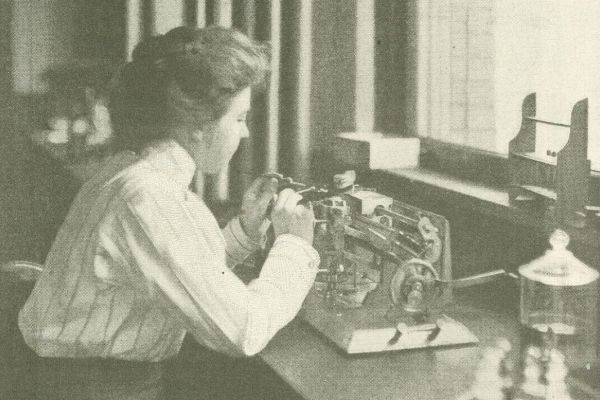

Dr. Park planned and organized the entire medical facility, including separate wards for men and women, a kitchen and patient dining room, an operating room, a morgue — and even a “crèche” (day care center) where mothers could leave their babies in the care of a nurse before heading off to explore the fair. Staff included five doctors and a dozen nurses. The Albany Medical Annals proclaimed it “a most perfect hospital service.”

Expecting the unexpected: medical and public health challenges

During the Pan Am’s six-month run, from May 1-Nov. 1, more than eight million visitors passed through the gates. In June the Buffalo Medical Journal noted “how well the health of the big fair is safe-guarded,” reporting that “during the first days of the exposition, Drs. Wilson and Kenerson, under Dr. Park’s direction, handled a small epidemic of measles and stamped out the disease without creating a panic. Few people knew that a portion of the midway was under quarantine rule for two weeks.”

That was one of many unexpected challenges faced by Dr. Park and his Medical Department. They had to step in when an elderly woman who was infected with pulmonary tuberculosis — a contagious and potentially fatal disease — was discovered making cigars for sale, and when various performers did not keep their stables or living quarters clean. The Albany Medical Annals recounted how the medical staff even “removed a spike from the foot of Big Liz,” an elephant on display at one of the attractions.

Dr. Park also mentioned in his final report that visitors sometimes stopped by the hospital to ask for free drugs or permission to take a bath in a hospital tub.

Rules — and humanity

Unusual complications led Dr. Park to bend his own rules on a few occasions — for example, after he performed an emergency appendectomy on a foreign-born man who worked at one of the fair’s many concession stands. Under a policy set by Dr. Park himself, the man should have been sent to another hospital for recovery after the operation. But the patient did not speak English, so Park kept him at the Emergency Hospital on the fairgrounds, where he would be close to friends and family who could translate for him, “so that his wants could be made known.”

Still, there was no rule-bending when it came to patient privacy. When “reporters and newspaper men sought details regarding our patients” in order to write sensational stories about accidents or visitors’ medical conditions, Dr. Park made it clear to his staff that “patients should be afforded the same privacy that their own homes would furnish, and absolutely nothing was [to be] given out from the hospital regarding any individual or case.”

By the time the fair closed, the Medical Department had treated 5,567 people, providing care for:

- Numerous minor wounds, burns, sprains, heat exhaustion, and stomach upsets

- 78 fractures

- Six gunshot wounds

- Three cases of electric shock (two resulting in death)

- Two births

- Measles, mumps, malaria, and syphilis

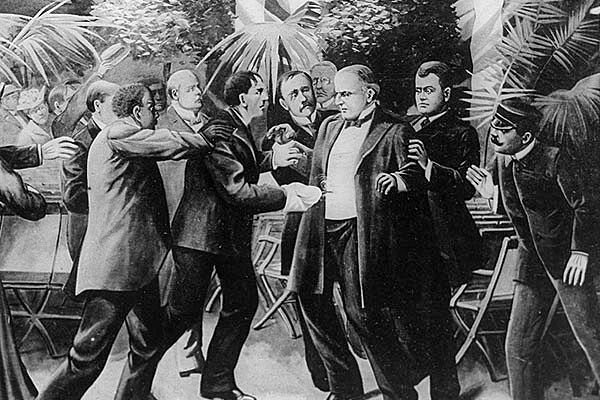

Those cases paled on September 6, 1901, when the Pan Am Emergency Hospital became the focus of a life-or-death drama surrounding the assassination of President William McKinley.

Read the Cancer Talk article "One Day in September" for that part of the story.

We Set the Model

50 years as an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center and more than a century leading the way. Learn more about Roswell Park's place in history as we became a model for other cancer centers around the world.

Explore the Pan Am:

- Read Dr. Park’s detailed Report of the Medical Department of the Pan-American Exposition.

- Watch Thomas Edison’s films of the Pan Am.

- The fairgrounds of the Pan Am were set between Elmwood and Delaware avenues, stretching from the Delaware Park Casino on the south to just past Great Arrow Ave. on the north. See a 1901 map of the Exposition overlaid on a 2007 satellite photo.