Journalists often use war terminology when referring to the COVID-19 pandemic: Healthcare workers are on the front lines as they battle an unseen enemy. As we mark National Nurses Day and the beginning of National Nurses Week, it’s fitting to remember that in the United States, the first professional training programs for nurses grew out of the Civil War.

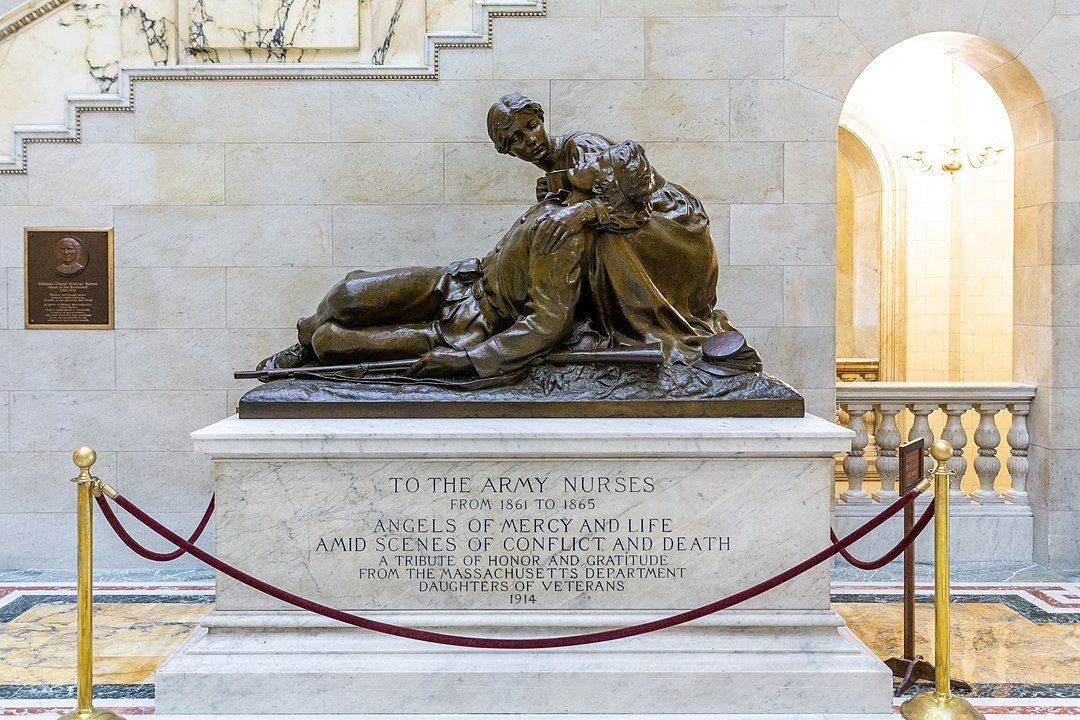

No other war in American history has resulted in greater loss of life. In the four years of conflict between 1861-1865, more than three million men went into battle, and an estimated 620,000 died. For every man who died on the battlefield, two more died of disease.

During the first months of the war, the nurses in an Army hospital were mostly soldiers who were themselves recovering from disease or injury. When they began to feel better, they were pressed into caring for others who were sicker. One soldier described the insanity of the system: “In the hospital, men lie on rotten straw...the nurses are convalescent soldiers, so nearly sick themselves that they ought to be in the wards, and from their very feebleness they are selfish and sometimes inhuman in their treatment of patients. If we could be sure of being half-way well cared for when we get sick or wounded, it would take away immensely from the horrors of army life.”

Things began to change in June of 1861 with the creation of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a private organization recognized by the federal government but run by civilians. Its mission: to generate financial support to meet the medical needs of the military; to acquire and distribute food, clothing and medical supplies to soldiers and military hospitals; and to organize military hospitals and camps and arrange transportation for the wounded.

The commission also recruited and managed nurses. They could choose pay of either $12 per month or 40 cents per day plus meals. Candidates had to be:

- Female, between ages 35-50

- In good health and of decent character

- Able to commit to at least three months of service

- Obedient to regulations and supervisors

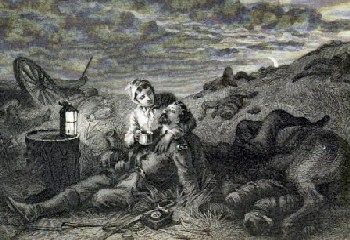

Nurses worked in hospitals, field hospitals, and even on the battlefield after the firing had stopped.

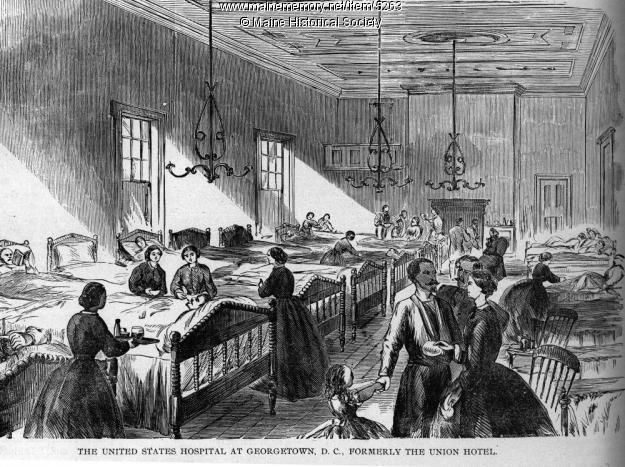

Louisa May Alcott served as a nurse at this hotel-turned-hospital in Washington, DC.

Nuns from various religious orders also served as nurses, and there were women and men who served as nurse volunteers — just not in an official capacity.

No previous training was required to be a nurse, because no training programs existed. For the most part, women learned nursing from their mothers. If they could read and were very lucky, they might have a copy of the 1837 handbook The Family Nurse to refer to when caring for the sick and elderly at home. Otherwise they learned on the job.

Nurses’ duties varied depending on whether they served in hospitals, field hospitals close to the battlefields or on the battlefields after the fighting stopped. In some hospitals they assisted surgeons. In most hospitals they changed dressings, washed patients, prepared meals and fed the men, emptied bedpans and chamber pots, administered medications and wrote letters to the men’s families at home.

Driven by compassion, nurses of the Civil War worked long hours in extremely difficult conditions, put their own lives at risk and often suffered the outright contempt of surgeons and military officials. But by the end of the war, they had earned the respect of their patients and the medical community, who had come to rely on them.

After the war, a Wisconsin soldier who had been treated at the Adams Hospital in Memphis wrote, “A careful observation of over two years has taught me that nursing is fully as important as medicine. In the wards where there was the best nursing, there were always the fewest deaths.” (In fact, disease rates in wards overseen by the U.S. Sanitary Commission were approximately half those of other facilities.)

In 1869, four years after the war ended, the American Medical Association convened a committee to investigate whether there was a need for nurse training programs, concluding later, “It is just as necessary to have well-trained, well-instructed nurses as it is to have intelligent and skillful physicians.”

The first formal nurse training program in the U.S. was established at the New England Hospital for Women and Children in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1872. Linda Richards, the first graduate of the intensive 16-month program, went on to establish the system we use today of maintaining individual medical charts and records for patients.

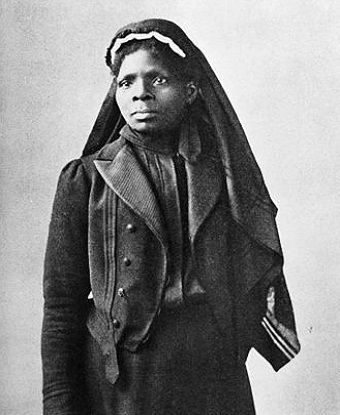

In 1878, 33-year-old Mary Eliza Mahoney, the daughter of freed slaves, enrolled in the same program. Out of a class of 40, she was one of only four women who graduated, becoming the nation’s first formally trained black nurse. She later co-founded the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses.

Our highly skilled nurses at Roswell Park continue that legacy. Among many other roles, they contribute to clinical research, support surgeons in the operating room, educate patients and families about issues critical to treatment and survivorship, and provide direct care to patients, sometimes specializing in such areas as chemotherapy or bone marrow transplants. Courageous and competent, they reflect the same spirit as the brave nurses of the Civil War.

Here are brief biographies of a few of those nurses.

Mary Ann “Mother” Bickerdyke (Mary Ann Ball), 1817-1901

In June of 1861, Mary Ann Bickerdyke traveled from her home in Galesburg, Illinois, to a military field hospital 350 miles away in Cairo, to deliver a load of medical supplies donated by her church. After witnessing the appalling conditions at the hospital, she decided that God had called her to change things.

She did not return home until after the war. Although she was not an official nurse recruit, over the next four years she traveled where she was needed most, establishing 300 field hospitals, attending to sick and wounded men in the wake of 19 battles — more than any other Civil War nurse on record — and organizing dietary kitchens and laundry services. The hospital in Cairo where she first began working earned a reputation as one of the cleanest in the nation — a major victory at a time when more men died of disease than on the battlefield.

Bickerdyke had attended Oberlin College in Ohio, later working as a nurse during an 1837 cholera epidemic in Cincinnati. When her husband died shortly after they moved to Illinois, she supported her two young sons by continuing to work as a nurse and was known for her special knowledge of medicinal plants and herbs.

As a military nurse, she was known for breaking rules, bucking authority and doing whatever she could to ensure that the men in her care were fed, comfortable and given the best chance of recovery. Her love and compassion inspired them to call her “Mother Bickerdyke.”

When the medical director of a field hospital ordered his men to burn a load of used and reeking blankets, stiff with blood and filth, Bickerdyke secretly confiscated them, because her men were freezing and there were no other blankets to be found. She boiled water in huge cauldrons so the blankets could be washed. Then, to kill any fleas, lice and bedbugs, she added something to the water that was used commonly to deodorize sewage — carbolic acid, which Joseph Lister would later promote as a means of preventing infection. Unwittingly Bickerdyke had disinfected the blankets.

Bickerdyke once found a surgeon drunk in the back room of a military hospital and tossed him out on his ear. When the surgeon complained to Gen. William T. Sherman, Sherman famously replied, “Well, if it was Mrs. Bickerdyke, I can’t help you — she outranks me!” Sherman’s respect for her was so great that when he and his soldiers were honored in a postwar parade in Washington, DC, he invited her to ride beside him.

Dr. J.J. Woodward, a surgeon with the 22nd Illinois Infantry, once described Mother Bickerdyke as “strong as a man, muscles of iron, nerves of finest steel, sensitive, but self-reliant, kind and tender; seeking all for others, nothing for herself.”

At one point during the war, Bickerdyke was taken in for questioning by a sentry after she was seen crossing the battlefield at night with a lantern in her hand. She told the commanding officer that she could not sleep, thinking there might be one man still alive and undiscovered, suffering alone in the dark.

Susie King Taylor (Susan Baker), 1848-1912

Born into slavery in Georgia, at the age of seven Susie King Taylor was allowed to travel to Savannah to live with her free grandmother. Although teaching slaves to read was a crime in Georgia, the little girl was educated at a secret school taught by black women, and later by a white playmate.

Taylor was just 13 when the Civil War began. The following year, she and members of her family escaped and eventually made their way to the protection of Union troops on the South Carolina Sea Islands. She married Edward King, a black noncommissioned officer with the 33rd United States Colored Troops, and eventually became a nurse for her husband’s regiment.

The great-granddaughter of a noted midwife, Taylor had learned to prepare and administer medicinal roots and herbs — knowledge that served her well as a nurse. She also came up with ingenious solutions when supplies ran out, especially in areas close to the fighting. Once when she had little on hand to feed her patients, she mixed turtles’ eggs with condensed milk to make “a very delicious custard.”

She was also prepared to defend herself and her patients: “I learned to handle a musket very well while in the regiment, and could shoot straight and often hit the target. I assisted in cleaning the guns. I was also able to take a gun all apart and put it together again.”

In the midst of war, she endured the “roar and din” of the guns that “jarred the earth for miles.” She often walked to Fort Wagner to watch the shelling of Charleston, stopping to move the skulls of fallen soldiers from the path.

When smallpox broke out in her camp in February of 1863, she continued caring for a man who was infected, as she recounted later in her autobiography, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd United States Colored Troops. “Edward Davis had it very badly. He was put into a tent apart from the rest of the men, and only the doctor and camp steward, James Cummings, were allowed to see or attend him; but I went to see this man every day and nursed him. The last thing at night, I always went in to see that he was comfortable. I was not in the least afraid of the small-pox. I had been vaccinated.”

While some nurses, both black and white, earned wages during the war, “I gave my services willingly for four years and three months without receiving a dollar,” King wrote afterward. “I was glad, however, to be allowed to go with the regiment, to care for the sick and afflicted comrades.”

Reflecting on the work of wartime nurses, she added, “It seems strange how our aversion to seeing suffering is overcome in war. We are able to see the most sickening sights without a shudder. Instead of turning away, how we hurry to assist in alleviating their pain...”

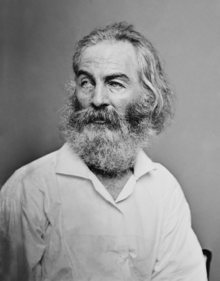

Walt Whitman, 1819-1892

Although the U.S. Sanitary Commission recruited only women as nurses, men, too, served in that role by simply showing up and going to work. After learning from a newspaper article that his younger brother, George, had been wounded at the battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia, journalist Walt Whitman left New York City to try to find him. Whitman was deeply affected by the grim conditions he saw at the field hospital where his brother was recovering. He stayed on for several days, helping bury the dead and providing comfort to the wounded, sick and dying.

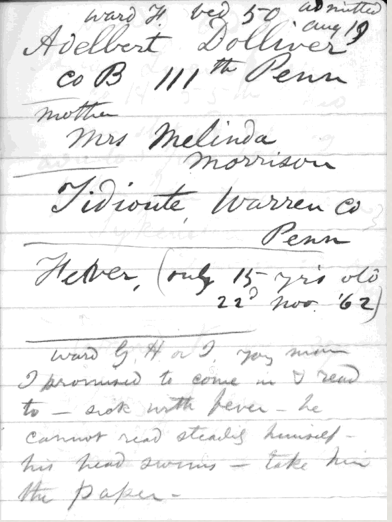

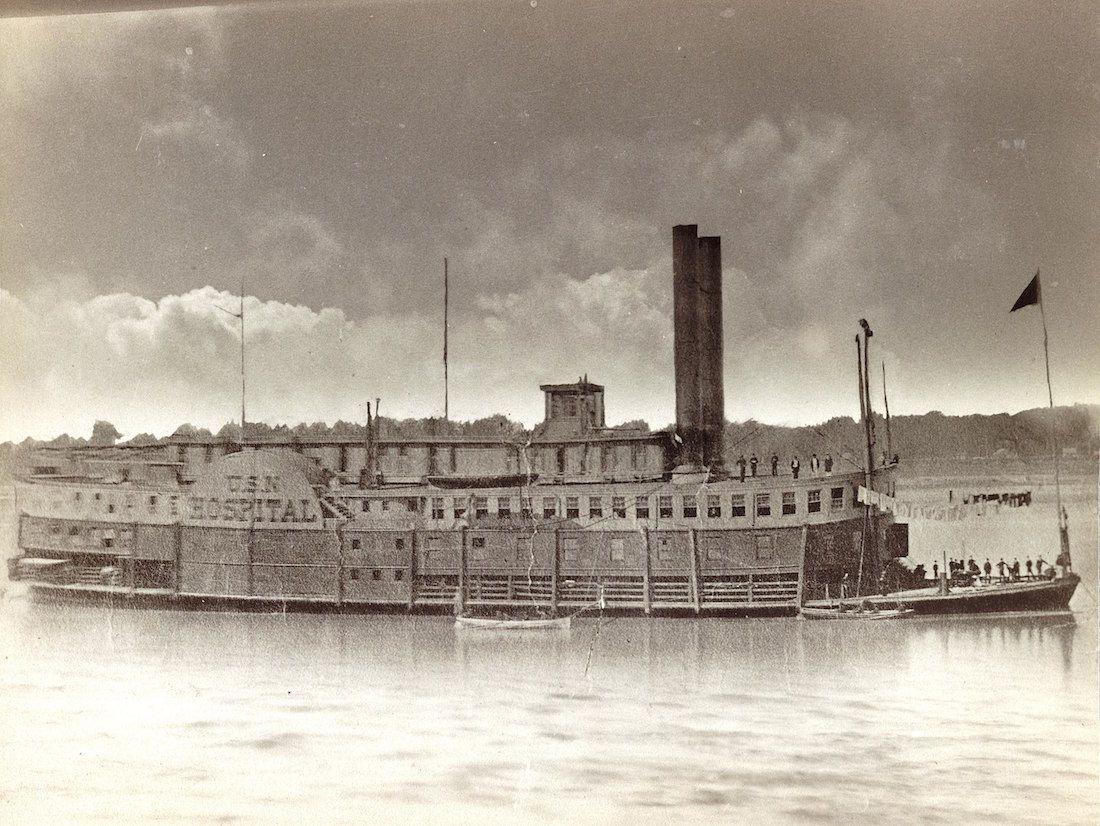

Later he accompanied a group of wounded soldiers as they were transferred by steamboat to hospitals in Washington, DC. For the next three years, Whitman remained there to serve as a nurse at various hospitals, assisting surgeons and even holding men as their limbs were amputated. He wrote letters for the illiterate or those too weak to hold a pen, distributed oranges or candies, and offered words of comfort and encouragement. His work as a nurse inspired much of his writing, including Drum-Taps, a collection of poetry about the war. Today he is considered one of America’s greatest poets.

A wartime article published in The New York Herald described Whitman making his rounds in the hospital with “a basket or haversack on his arm. From cot to cot soldiers called him, often in tremulous tones or whispers. As he took his way toward the door, you could hear the voices of many a stricken hero calling, ‘Walt, Walt, Walt! Come again! Come again!’”

Louisa May Alcott, 1832-1888

Today Louisa May Alcott is remembered mostly as the author of Little Women, but it was a series of magazine articles called Hospital Sketches that first brought her to the attention of the American public. Later compiled into a book, the articles — written under the amusing name Nurse Periwinkle — described her work as one of the U.S. Sanitary Commission’s first nurse recruits of the Civil War. Hungry for the truth about the conditions in which their sons, fathers and husbands were being cared for in military hospitals, readers snapped up copies of the magazine as each new installment hit the newsstands.

Alcott was assigned to a hospital in Washington, DC, that had been converted from a hotel. Unlike many other writers of the day, she did not hold back in describing the conditions of the place, the work she faced or the suffering of the men. An influx of wounded, some of whom had been lying on the battlefield for days, brought in “the vilest odors that ever assaulted the human nose” — and it was her job to bathe them. A Virginia blacksmith, shot through the lungs, cried out, “For God’s sake, give me air!” Without “the merciful magic of ether,” men waited in excruciating pain to have their legs amputated.

Alcott and another nurse slept on narrow iron beds in a room with broken windows and the sound of rats scrabbling in the closet. They ate mostly canned beef (obviously left over from the Revolutionary War, she joked), bread that seemed to be made of sawdust, and “stewed blackberries, so much like preserved cockroaches.”

But she also shared the poignant moments that made it all worthwhile: laughing with an older man as she washed him; delivering books, games and flowers to men in one of the wards; and putting her arms around a dying man who was alone and far from home.

When Alcott later contracted typhoid, her “sister nurses” surrounded her “like a flock of friendly ravens,” feeding and comforting her. “One of the best methods of fitting oneself to be a nurse in a hospital is to be a patient there,” she wrote afterward. “For then only can one wholly realize what the men suffer and sigh for; how acts of kindness touch and win; how much or how little we are to those about us.”

Alcott was sent home to Massachusetts to recover. After the war, she worked with Harriet Tubman, teaching former slaves to read and write. Although she never returned to nursing, she expressed that wish at the end of Hospital Sketches: “The next hospital I enter will, I hope, be one for the colored regiments, as they seem to be proving their right to the admiration and kind offices of their white relations, who owe them so large a debt, a little part of which I shall be proud to pay.”

Contrabands

Slaves who escaped to freedom or who were liberated by the Union Army were called “contrabands of war,” or simply “contrabands.” Many attached themselves to Union soldiers for protection and traveled with them, providing critical services as teamsters, laborers, cooks, launderers and nurses. Some male contrabands went on to enlist with the U.S. Colored Troops.

Ann Bradford Stokes, Harriet Tubman and Susie King Taylor, profiled elsewhere in this article, were among the contrabands who served as nurses during the Civil War. Often these women brought valuable skills to their work, having learned from their mothers or grandmothers how to use herbs and roots to treat wounds, fever and various illnesses.

Learn more about the work of contrabands: “Binding Wounds, Pushing Boundaries: African Americans in Civil War Medicine, an online exhibit of the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Ann Bradford Stokes (Ann Bradford), approx. 1830-1903

Born into slavery, Ann Bradford Stokes escaped from a Tennessee plantation in 1863 and found her way to the Union ship U.S.S. Red Rover (pictured, right). She became one of the first women to serve as a nurse in the U.S. Navy and was the first to receive a pension based on her own military service.

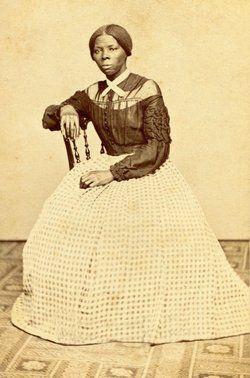

Harriet Tubman (Araminta Ross), approx. 1822-1913

Born a slave in Maryland around 1822, Harriet Tubman is known best as the most famous conductor of the Underground Railroad, but she also served as a spy, scout and nurse for the Union Army.

In 1849, after learning that she would probably be sold to cover her master’s debts, she escaped to Philadelphia. She then joined the Underground Railroad and returned to Maryland to smuggle more than 70 other people to freedom, including her elderly parents. Later she was authorized by the U.S. Army to organize and lead a team of scouts to map and infiltrate enemy territory in the South. During the 1863 Combahee Ferry Raid, she became the first woman to lead an armed assault in the Civil War, helping to free another 750 slaves.

Tubman also worked with Col. Robert Gould Shaw as he and the men of the 54th Massachusetts — a black regiment featured in the film Glory — prepared for the second assault on South Carolina’s Fort Wagner. Recalling the battle later, she said, “And then we saw the lightning, and that was the guns; and then we heard the thunder, and that was the big guns; and then we heard the rain falling, and that was the drops of blood falling; and when we came to get the crops, it was dead men that we reaped.”

During the war, Tubman served as a nurse at hospitals in Hilton Head and Port Royal, South Carolina; Fort Monroe, Virginia; Washington, DC; and Fernandina, Florida, treating both soldiers and contrabands (freed slaves). As a nurse she drew on the knowledge her mother had passed on to her of herbs, roots and other home remedies. She earned a reputation among army surgeons for being able to cure dysentery, leading the War Department to request her services at a Florida hospital where men where “dying off like sheep.” Despite her close contact with people suffering from smallpox and other highly infectious diseases, Tubman never fell ill.

In 1908 she established the Harriet Tubman Home for Aged and Indigent Colored People in Auburn, NY. She was buried with military honors at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn when she died in 1913.

Clara Barton (Clarissa Harlowe Barton), 1821-1912

At the beginning of the Civil War, some people questioned whether women were capable of serving under battle conditions and enduring the horrors of caring for the wounded. As a nurse for the Union Army, Clara Barton served exclusively on the battlefield, going out immediately after the firing stopped. Often she had to stop to wring the blood from her long skirts. When an exploding shell sliced into a soldier’s artery, she quickly applied a tourniquet to keep him from bleeding to death. On another occasion, a bullet tore through her sleeve and killed the man she was treating.

Barton took care of the wounded after some of the war’s bloodiest battles, sometimes working for 48 hours straight. Stricken with typhoid after the Battle of Antietam in 1862, she went right back to work after recovering. A surgeon who worked beside her wrote, “General McClellan...sinks into insignificance beside the true heroine of the age, the angel of the battlefield.”

Born in Massachusetts, Barton’s interest in nursing began at the age of 10, when her brother sustained a serious head injury. She took an active role in his care and administered his medications.

Although she later became a teacher and then a patent clerk, she was lured back to nursing in April of 1861, when southern sympathizers attacked Union soldiers in Baltimore, Maryland, mere days after the war began. The wounded were evacuated to Washington, DC, where the Senate Chamber of the Capitol had been transformed into a hospital. Barton hurried to deliver food and other supplies that she had at home, but after seeing how much was needed, she rallied the community to give more.

“I have no right to these easy comfortable days and our poor men are suffering and dying,” she wrote. “I’m well and strong and young — young enough to go to the front. If I can’t be a soldier, I’ll help soldiers.”

Barton set up a collection and distribution system for supplies, and this continued to be a major focus of her work throughout the war. In 1862 she was granted official permission to deliver those supplies directly to battlefields. From that time on, Barton accompanied the Union Army to serve wherever she was needed most, cooking, assisting surgeons, caring for the wounded.

Once when she arrived on a battlefield with bandages and medicine, she found surgeons trying to dress wounds with corn husks. Following a battle in Virginia, she arrived at a field hospital late one night with a wagonload of supplies, leading a frazzled surgeon to say, “I thought...that if heaven ever sent out an angel...she must be one.”

After the war, Barton traveled to Europe, where she learned about the International Committee of the Red Cross, which had been founded in Geneva, Switzerland, just two years earlier. When she returned to the U.S., she recruited prominent Americans, including Frederick Douglass, to work with her in establishing the American Red Cross.