Your blood carries a wealth of information. That’s why certain blood tests can detect conditions of concern before symptoms appear. For example, tumor markers in your blood can help doctors figure out which treatment might work best for your cancer, indicate your prognosis or reveal whether your cancer has returned or gone into remission.

Blood tests are also used to monitor your condition, by checking:

- How well your treatments are working

- Whether it is safe for you to continue your current treatment plan

- The effects of your medications

- Whether any of your blood cell types are below or above the normal range, and whether your blood is clotting normally

- The levels of electrolytes, minerals, hormones, oxygen and carbon dioxide in your blood

- Whether you have an infection

- How well your organs and systems are working

What are the components of blood?

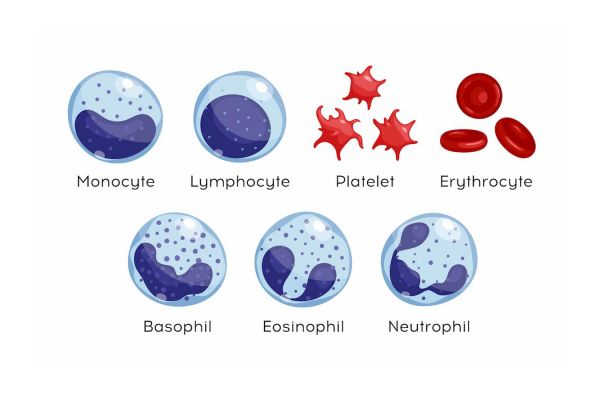

Blood is a combination of four key elements: plasma, red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs) and platelets (PLTs). Plasma is the liquid part of your blood that carries nutrients, hormones and proteins to your cells and carries away waste.

Your doctor may order a Complete Metabolic Panel (CMP) or Basic Metabolic Panel (BMP). A CMP is a group of 14 tests that measure electrolytes, proteins, liver enzymes and kidney waste products in the blood. A BMP omits the liver and protein tests.

Before considering the results of specific tests, remember that the “normal” ranges listed below are averages for healthy people, but ranges can be different for men or women or people of different age groups. Use the ranges on your lab results report when interpreting your results.

About red blood cells

Red blood cells, also called erythrocytes, or RBCs, make up 40-45% of your blood. They live for 100-120 days and are continuously replenished with new RBCs, which are made in the bone marrow. RBCs contain hemoglobin, a protein that carries oxygen from your lungs to the rest of your body. A hematocrit shows what percentage of your blood is made up of RBCs. Your RBC count is usually interpreted with your hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

Test | Reasons for Low Count (Anemia): | Reasons for High Count (Polycythemia): |

|---|---|---|

Red Blood Cell Count Range: 4.2-5.4 (women) Hemoglobin: 12.5-15.5 Hematocrit: 36-47 |

|

|

Other tests examine the characteristics of RBCs. RBCs are usually the same general shape and size, but certain conditions (for example, anemia or thalassemia) can affect their appearance:

- Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV): Measures a single red blood cell (76-100)

- Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH): Average amount of hemoglobin in a single RBC (27-34)

- Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC): Average concentration of hemoglobin in a single red blood cell (31.5-37)

- Red Cell Distribution Width (RDS): The variation in the size of red blood cells (11.5-14.5)

About platelets

Platelets, also called thrombocytes, are tiny fragments of cells that are vital for normal blood clotting. They come from very large cells (megakaryocytes) in the bone marrow and are released into the blood. When there is an injury to a blood vessel or tissue and bleeding begins, platelets help stop it by clumping together. They will also release chemicals that cause more platelet clumping.

Test | Reasons for Low Count (Anemia): | Reasons for High Count (Polycythemia): |

|---|---|---|

Platelets 150,000 – 450,000 per microliter, which may be written as 150-450 x 10⁹/L | Conditions that slow production of platelets or speed up their use or destruction:

|

|

Mean Platelet Volume (MPV) and Platelet Distribution Width (PDW) provide more information about the cause of an abnormal platelet count. These tests are done by machine.

- Mean Platelet Volume (MPV): The average size of your platelets (range 8-12). A high MPV with a low platelet count may indicate that the platelets you make are going into circulation very quickly. A low MPV is linked to inflammatory bowel disease, chemotherapy and certain types of anemia.

- Platelet Distribution Width (PDW): Tells how similar the platelets are in size (range 25-65). A high PDW means there is a great variation in size, which may be associated with vascular (blood vessel) disease or certain cancers.

Sometimes during the test, platelets stick together and the machine gives a false reading, interpreting it as fewer, larger platelets. In that case, the lab may do a blood smear and directly examine the platelets under a microscope.

Understanding clotting studies

Two tests measure how well your blood clots and how long clotting takes. These are called the Prothrombin Time / International Normalized Ratio (PT/INR) and the Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT or aPTT ). They can be used to establish your baseline (starting point) before treatment, or to monitor your response to anticoagulation medications such as warfarin and heparin.

The process of blood coagulation and clotting involves a series of reactions that focus on activating clotting factors in your blood. There must be enough quantity of each factor, with each factor working properly, for normal clotting to occur. Too little of these factors can lead to excessive bleeding, and too much may lead to excessive clotting. If your PT/INR or PTT is abnormal, your doctor may order more blood tests to measure the amounts of each clotting factor in your blood.

For more information, see the Roswell Park publication “Understanding Your Blood Tests.” You’ll find it online in the Patient Education Library in the MyRoswell patient portal, or you can pick up a copy of the brochure from The 11 Day Power Play Cancer Resource Center or ask your nurse in your center.